Readers of the park’s blog may remember my previous discussions in 2014 regarding “The Home of a Rebel Sharpshooter”, the famous photograph of the dead Confederate soldier in Devil’s Den taken by Alexander Gardner and his photographers in July 1863 and my interpretation of the regiment to which the deceased soldier belonged- the 15th Georgia Infantry of “Rock” Benning’s Brigade. I based my analysis on not only the series of photographs taken of this particular body but textural resources including post-war recollections, reports in the Official Records, and photographic studies by experts including Bill Frassanito and Garry Adelman. Since those posts, I recently revisited the circumstances regarding this series and had the fortune of discussing my premise with a number of individual researchers including Mr. Scott Fink, currently undertaking a study of photography at Gettysburg and with whom I’ve discussed the sharpshooter series specifically. Scott recently offered a hypothesis and further analogy of the individual in these famous images on Facebook and has allowed me to share it with our readers.

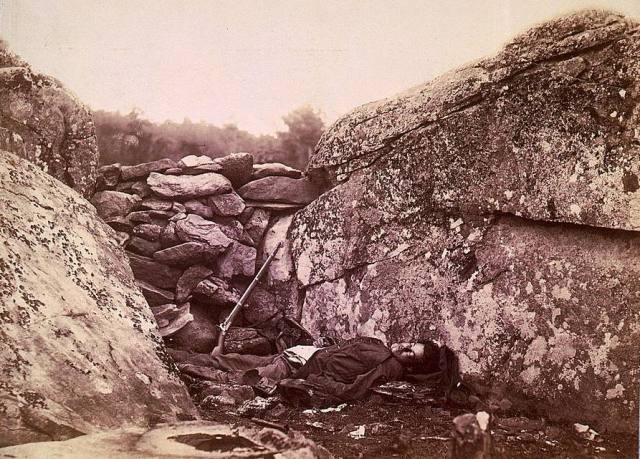

The final scene captured by Gardner’s camera at Devil’s Den, the fallen sharpshooter behind the stone barricade above Devil’s Den. The photographers carried the body to this location from where they had found him approximately 40 yards downhill from this position. (Library of Congress)

The focus of my previous posts was to try and identify, at minimum, the brigade or regiment to which this young man belonged. Any further attempt to identify him by name is a near impossible task given the lack of photos of soldiers in the units that fought in this area to compare with the subject in the Gardner images, almost non-existent information on the uniform details and comparisons, and few surviving accounts of exactly who fell in that area on July 3, 1863. As I lamented, he had a name, a family, and a profession before winding up as a photographic subject but uncovering an identity to associate with the body is, and will always be, a shot in the dark. (One footnote to this discussion is that I am also aware of claims the body has been previously identified as William Langley of the 1st Texas Infantry, a soldier in the 4th Virginia Infantry, and a “real sharpshooter” who died on that exact spot, crushed by the collapse of the stone barricade, all of which I’ve evaluated and ultimately found to have little merit or could not be historically supported.)

Remarkably, Scott may have uncovered a probable candidate- a Georgian named John Rutherford Ash: “As the topic of the Devil’s Den Sharpshooter is brought up often, I thought I would put in my two cents,” Scott wrote in this January 10 post. “I have noticed that whenever the subject comes up, that the same controversy is discussed about what order the photographs were taken and the role the soldier played in his unit. What is lost here is the tragedy of this iconic photograph. Regardless of where the body was moved to or from, the young soldier lost his life in Devil’s Den. I’m more interested to find out who this soldier was, rather than the movement of the body or whether he was a sharpshooter or not.”

Scott’s mention of the controversy surrounding movement of the body is inconsequential to this discussion, but I will add that I stand by the order of the photographs based on Bill Frassanito’s research, noted as such in my previous posts on this subject and the heart of the matter in that order is how this soldier’s body wound up in the location where Gardner and company found it, near the remains of a small bivouac behind large boulders on the southwest side of the ridge. Was this lone casualty the result of combat more than a day after the intense fighting had taken place at this site on July 2? I believe so, and Scott explains his hypothesis further:

“In short, the Georgia brigade (Benning’s) occupied both camera locations (in Devils’ Den where the subject was photographed by Gardner) till 7 pm on July 3rd. It is doubtful that any bodies from the fighting of the 2nd would be left unburied throughout the 3rd. (Benning’s) Brigade was the last… to withdraw and they were being surrounded on both sides by McCandless on his left and the US Sharpshooters on his right. In order to get out of this predicament Benning decided to “Pike Out”… called his guidons to post and for his regiments to form up behind them. The area he chose was the exact spot where I believe Gardner discovered the body at the downhill location (where the body was first photographed). By doing that genius maneuver Benning saved a lot of lives and got his brigade out with slight loss.”

(A note about the time of the retreat. General Benning’s report in the Official Records states the withdrawal occurred at 4:30 PM, but he later corrected that to 7 PM, the factual time frame when Hood’s and McLaws’ Divisions of Longstreet’s Corps withdrew to a designated defensive line on Seminary Ridge and its southern extension, Warfield Ridge. )

Though brief, Scott provided a well-constructed analysis of the incident. It would have natural for Benning and his commanders to take advantage of the reverse slope of Devil’s Den to quickly reform their regiments to begin the withdrawal, but the troops did not get out unscathed. Both the 2nd and 20th Georgia Infantry regiments reported casualties during this process. Both had been in positions exposed to Union sharpshooters and artillery from which to extricate themselves before the rally to begin the retreat. Apart from mention of the losses in reports published in the Official Records (Volume 27, Part II), Scott mentioned an account by William Houghton, Company G, 2nd Georgia who testified years later that his regiment “formed up under ‘heavy fire’ where ‘a few went down here and there.’”

Was one of the “few” from Houghton’s regiment who fell on the hillside late on July 3 this soldier, discovered by Gardner and photographed three or four days later? It’s intriguingly possible since the 2nd Georgia had to withdraw to this area from its position in the Devil’s Kitchen and Slaughter Pen, exposed all the while to a number of parting shots from Federal skirmishers and a small group of the 1st US Sharpshooters, detached to the Fifth Corps to counter the activities of Confederate sharpshooters. The reverse slope of the ridge and specifically the large boulders where the body was first discovered would have provided the soldiers of the 2nd Georgia the cover needed to form ranks prior to racing to the protection of the trees on Warfield Ridge.

Unfortunately, documenting Scott’s proposed location as the first where the regiment formed is a near impossibility given the lack of Confederate testimony regarding the events on July 3 but I tend to agree with Scott’s premise based on the natural features of the landscape at that location which offered brief but necessary protection and quite possibly where some of the “few who went down here and there” had fallen or were hastily carried to by comrades, only to have been forced to leave the dead or dying man behind. And a reminder to reinforce this point; as I described the scene in previous posts, the remains of a small campfire and bivouac near the body when first discovered lends me to believe the soldier fell at that location during the last of its occupation by friendly troops. Though we tend to believe Civil War soldiers were nonchalant about the dead who lay scattered about the battlefield, I think it highly doubtful the men who sat around that small fire could have been so blatantly cold as to not have removed the body or made an attempt to bury him since other casualties had been carried away and buried by comrades overnight of July 2 and during the morning hours of July 3.

Having proposed the area where the 2nd first rallied, Scott then presented an intriguing photographic comparison between the “sharpshooter” and the soldier mentioned earlier in this post: “Among the dead was John R. Ash from the 2nd Georgia, Co. A. By comparing a photo of John Ash from most likely 10 years earlier the similarities are striking. They share the same nose, mouth, eye brows, chin, hairline and ears.”

Detail of comparison between portrait of John Rutherford Ash, Company A, 2d Georgia Infantry, and the face of the deceased soldier in Devil’s Den. The arrow denotes a detail in the hairline of both. Ash was approximately 13 when the portrait was made and two months shy of his 26th birthday when he was killed at Gettysburg, an age comparable to the dead soldier. (Georgia State Archives, LOC, Scott Fink, 2018)

Born on September 28, 1837, John Rutherford Ash resided in Banks County, Georgia, where he enlisted on July 10, 1861, in the “Banks County Guards”. Assigned to the 2nd Georgia Infantry Regiment as Company A, Ash and his comrades were sent to Virginia where the regiment was engaged in all of the Army of Northern Virginia’s campaigns, from Yorktown to Gettysburg during that fateful summer of 1863. Ash was marked as present or accounted for until wounded during the Seven Days battles, but rejoined his regiment in time for the 1863 campaigns. Noted as killed at Gettysburg July 2, 1863 in the Roster of the Confederate Soldiers of Georgia, 1861 to 1865, the date of his death is inscribed on a memorial headstone in a Georgia cemetery as July 4, 1863 (See Travis and John Busey, Confederate Casualties at Gettysburg, A Comprehensive Record, Vol. 1, p. 266). Is the difference in dates based on information sent the family from Ash’s comrades versus the official roll of casualties sent to the state’s adjutant general? It would seem so but further research into the family’s records and the possibility of a surviving letter would confirm my suspicion.

Scott also provided additional analysis of a detail in the image: “(T)he soldier seems to have the number ‘2’ and the letter ‘A’ etched into the coating of his haversack. Could this mean the 2nd Georgia (C)ompany A, the unit in which Ash belonged to? Perhaps, but this is still a working theory.” Likewise, I have looked at the details on the items attached to the soldier and the markings that he propose are difficult to discern given the amount of dirt scuffs and light reflection off the paint of the haversack’s finish, but the figure of a “2” is certainly visible in a blow up and the high resolution image.

Though difficult to discern, the form of a painted “2” appears on the soldier’s haversack in this detail of the original image. (LOC; Scott Fink, 2018)

It was not uncommon for unit numbers to be painted on knapsacks and haversacks. Though surviving examples are quite rare, especially with a provenance to a Confederate soldier, the practice of marking maybe more widespread than at first believed.

Scott’s research that he willingly presented on his Facebook post is not only intriguing but also offers we historians an opportunity to re-evaluate the events that took place in the evening hours of July 3, 1863 at Devil’s Den. Such is the positive power of the internet and how we can communicate in our study of the past, to uncover and discuss incidents glossed over in reports and recollections as minor details, which are not so minor when it was a matter of life or death and the loss of a loved one whose likeness has appeared in countless books and magazines as an illustration of the Battle of Gettysburg.

I wish to thank Scott for allowing me to share his hypothesis and image comparisons with our readers. “Regardless if I’m correct or not,” Scott wrote on his January 10th post, “please remember that this soldier had a family who lost him in this terrible costly battle.” And in the end, isn’t that why we study these photos again- the young soldier whose family was saddened by the news of his death on a far away battlefield, where his regiment and name were lost in the chaos of battle? Ultimately, we may be getting closer to knowing more about this young Georgian than ever before, not only his regiment but a name as well.

-John Heiser

Historian, Gettysburg National Military Park

February 10 Chapter 1-2

February 10 Chapter 1-2