As winter finally fades, we are reminded by the appearance of flowers and greenery that Memorial Day must inevitably be approaching. There is always special meaning to the promise in the rebirth of spring, often nowhere more so than at the graves of a nation’s soldiers.

The Gettysburg Campaign produced approximately 10,000 dead. Of these, some 3,555 soldiers were buried within the Soldiers’ National Cemetery. At the time, all were believed to be exclusively soldiers of the Union, as popular sentiment quite clearly backed segregating the Rebels from the Union soldiers. Unknown at the time to both William Saunders, landscape architect of the cemetery, and David Wills, the project supervisor appointed by Pennsylvania Governor Andrew Curtin, a few plots did contain the remains of Southern soldiers; placed there purely by mistake. The vast number of fallen Confederates yet lay in mass graves, spread across the fields where they fell.

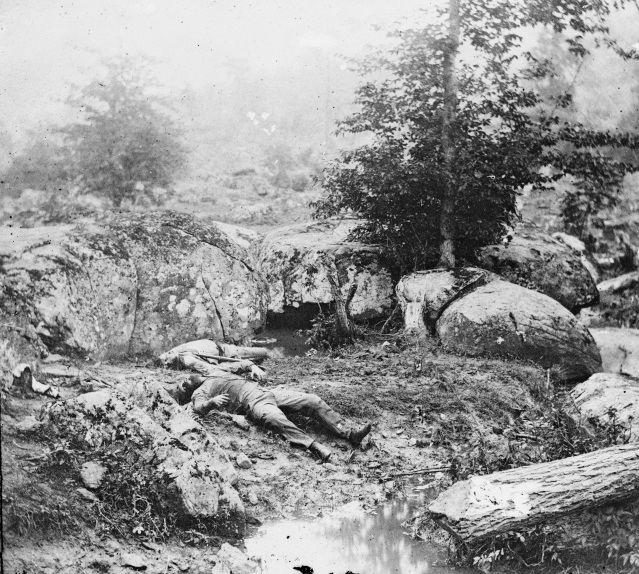

Confederate dead littered the battlefield, such as these men killed in the fighting at the “Slaughter Pen.”

In the spring of 1864, there had been scattered calls in the Gettysburg Sentinel to collect the “Rebel remains,” in the name of “a common humanity,” but the pressures and politics of war-time had forestalled such. Even impressive poetry, published in 1864, had pleaded the point – yet failed to convince. Finally, years following the close of the war and with waking opportunities presented by peace, in July of 1869, the old hero of Gettysburg, Gen. George Gordon Meade, stepped out to speak to the issue as part of his dedicatory address for the Soldier’s National Monument.

Maj. Gen. George Meade, commander of the Army of the Potomac, urged for the proper reburial of Confederate dead on the Gettysburg battlefield.

“When I contemplate this field, I see here and there marked with hastily dug trenches, the graves in which the dead with whom we fought are gathered. They are the works of my brothers-in-arms the day after the battle. Above them a bit of plank indicates simply that these remains of the fallen foe were hurriedly laid there by soldiers who met them in battle. Why should we not we collect them in some suitable place? I do not ask that a monument be erected over them. I do not ask that we should in any way indorse their cause or their conduct, or entertain other than feelings of condemnation for their cause. But, they are dead; they have gone before their Maker to be judged. In all civilized countries it is usual to bury the dead with decency and respect, and even to fallen enemies, respectful burial is accorded in death. I earnestly hope this this suggestion may have some influence across this broad land…”

In spite of Gen. Meade’s publicly – expressed statement, seeking governmental endorsement for the respectful removal of the Confederate dead, evidence of contrary sentiment had remained heavy. From the post-battle months into the early portion of the 1870’s, incidental retrievals of individual Confederates by determined Southern family members reflected the only inclination to address this issue. It would take the arrival of several elements – politics, money, and good intentions – to try and resolve it.

The immediate postwar period following any conflict is hard and filled with changes; this readjustment is significantly more so for the defeated, as those transitions often prove markedly more difficult. In the case of the beaten Confederates, their first priority was survival; accomplishing that, the task of replacing a war-ravaged infrastructure, and receiving the potential social and political implications of a Northern victory (all while attempting to reconcile the enormity of their previous sacrifices) lay ahead.

It was under this combination of pressures that a new form of entity entered the scene, collectively known as “Ladies Memorial” societies or associations. Differing and varied by region, they were yet united in their singular goal of rebuilding the shattered spirit of the Southern people.

War has not wholly wrecked us; still

Strong hands, brave hearts, high souls are ours–

Proud consciousness of quenchless powers–

A Past whose memory makes us thrill–

Futures uncharactered, to fill

With heroisms–if we will.

From “Acceptation”

Margaret Junkin Preston

Not surprisingly, after a time, was that one of the earliest projects seized upon in their efforts called for the removal of the Southern dead from the Gettysburg battlefield. In the absence of (often bankrupt or indifferent) state governments, these organizations took the lead in trying to recruit competent and connected individuals to assist them in achieving their goals.

In this instance, the Ladies latched onto the father and son team of the Weavers, Samuel and Rufus, who seemed best qualified from their knowledge of previous battlefield burials. David Wills had first hired Samuel to retrieve the fallen Federals for the Soldier’s National Cemetery in the fall of 1863. The Ladies, as well, approached the elder Weaver, who died shortly afterwards, in 1871, as the new project began. They then turned to his reluctant son Rufus to continue his father’s work.

Heeding their entreaties, Dr. Weaver was induced to lay aside his young medical practice in Philadelphia for (as it turned out, only partially fulfilled) promises of payment, to assist in the honorable cause of returning the remains of approximately 3,000 Confederates to Southern soil. He wound up devoting over three years to this effort.

For this particular project, his medical training proved an invaluable tool, as –

“(I) t required one with Anatomical knowledge, to gather all the bones, which [workmen could not do,] and regarding each bone as important and sacred as an integral part of the skeleton, I removed them so that none might be left or lost.”

Ultimately, these remains were destined to be placed into four large Southern cemeteries. Hollywood, in Richmond, received by far the largest number of fallen Confederates, at over 2,200 bodies; Oakwood, in Raleigh, was the recipient of 137; Laurel Grove, in Savannah, Georgia, saw the return of some 40; and Magnolia, in Charleston, South Carolina, with 82. Once brought home to be placed among their own, the remains of these men were predictably welcomed with all the respect and ceremony their fallen cause represented.

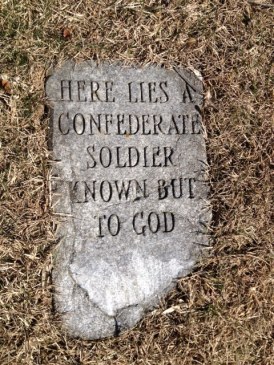

However, these organized Confederate removals did not mark the end of the story. By one estimate, over some 119 years following, there were at least thirty-nine later discoveries of remains, individually or in groups, Union, Confederate, or unknown. The hasty nature of warfare, coupled with the passage of time and scanty or unkempt records, made proper identification of these postwar reclamations nearly impossible. Even determining the former soldier’s allegiance often became something of a forensic challenge.

Many of these bodies were discovered in the battlefield area during the park’s Memorial Period, when the installation of modern avenues, digging for roadways, placement of curbs and gutter drains, etc., caused their accidental discovery. Some of them, believed to have been Federal soldiers, were removed to the National Cemetery, while on occasion, those thought to have been Confederates, once rediscovered, were often reburied near where they were found. A few of these were taken to Rose Hill Confederate Cemetery in Hagerstown, Maryland, while one was moved to Hollywood Cemetery in Richmond, Virginia.

Other nearly forgotten soldiers, all casualties of that summer of discontent, now sit quietly in a wider circle of distant cemeteries, reflecting the larger scope of military operations during the summer of 1863. These isolated cases mirror the ebb and flow of the complex and messy endeavor that had formed portions of the Gettysburg campaign throughout central Pennsylvania and northern Maryland.

Some of these may be found in the far–distant reaches of the traditionally presumed boundaries of the movements of the armies, such as Chambersburg, or Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. Other less-encountered Confederates rest in such places as Mount Holly Springs, PA, outside of Carlisle,

…or in Fairview Cemetery, in Mercersburg, PA (three CS dead, note the interweaving of the Confederate grave marker, the “1861” shield markers, Union and CS battle flags.)

Closer to Gettysburg, three residents “of the old gray gate,” rest around a single monument in the Old Mt. St. Mary’s Seminary Cemetery in Emmitsburg, MD.

Further north, three other Confederates are buried in a churchyard in Manada Gap, (near Hershey, PA); battle captives who perished in an unrecorded disaster connected with an iron furnace

and finally at Wrightsville, Pennsylvania, along the southern bank of the Susquehanna River, where a lone Confederate of those divisive days rests.

In varied ways, scattered, but in keeping with General Meade’s stated request, these lonesome souls had been buried “with decency and respect,” far from their native land; just as the term “native land” itself was being re-examined. This process had accelerated primarily as a result of the questions more sharply defined by the War itself.

This immense sacrifice, highlighted at each Gettysburg soldier’s grave, signifies a long and torturous process that continues even to this day, as we as a nation began to more precisely discern the freedoms that we now presently possess as Americans; and on occasion, the price we will pay to define and preserve them.

Unfortunately, distilling those answers is not always cleanly done; on occasion, the cost of doing so is high. As Abraham Lincoln stated, “Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure.” As we acknowledge the passage of just over 150 years from the issue of the Gettysburg Address across a war-ravaged countryside to the present Memorial Day, think upon the lessons of the stones that mark every American soldier’s grave, recalling the words from Lincoln’s Second Inaugural – “Fondly do we hope, fervently do we pray, that this mighty scourge of war may speedily pass away” – and reflect upon the meaning of the day.

Park Ranger Bert Barnett

I loved this post! Very well written, and the subject has always been fascinating to me.

Beautifully written and something most of us don’t think about.

Very well written. A poignant and differing look at the aftermath of the Battle. Thanks Bert!

Sorry, different, not differing!

Beautifully and thoughtfully written. Far too many Americans, both Union & Confederate, were left on farms and fields in both the North and mostly the South: some unburied or in shallow graves, often desecrated, without ‘decency or respect’. The deep wounds of this republic of suffering lent little interest or care for the identification and reburial of remains of the ‘enemy’, other than private citizens or groups. I am reminded of the words of then Col Joshua Chamberlain: “…on great fields, something stays. Forms change and pass, bodies disappear but spirits linger, to consecrate the ground for the vision place of souls…”

Wow, beautifully written, Mary Beth…..

Well done! I’m collaterally related to Margaret Junkin Preston, so thank you for quoting her.