When he awoke early on the morning of July 1, 1863, near the banks of Marsh Creek and several miles south of the town of Gettysburg, in south-central Pennsylvania, 2nd Lieutenant Gilbert Dickey’s first thoughts were most assuredly of his dear wife Rosetta. That day just happened to be their anniversary–their first anniversary–but instead of

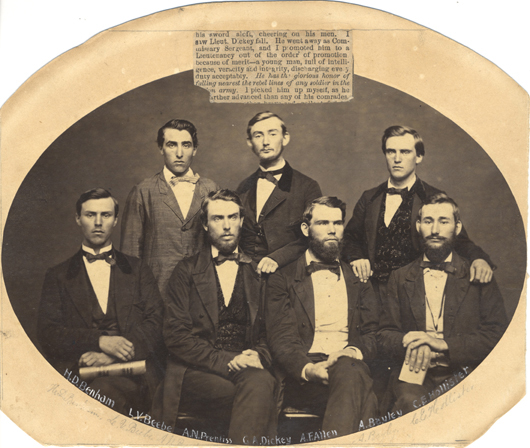

A Portrait Photograph of Gilbert A. Dickey, Wearing a Sergeant’s Uniform

[Courtesy of Michigan State University Archives and Historical Collection]

celebrating the happy occasion together, she was instead at home in far away Marshall, Michigan, some 530 miles from where he awoke that damp summer morning. Surely on so special a day Gilbert longed to be with Rosetta rather than waking up from an uncomfortable roadside bivouac, drinking brackish coffee, and gearing up for what promised to be yet another hot day. Yet, thoughts of home and of Rosetta would soon be interrupted when orders arrived for Dickey and his men to make their way post-haste toward Gettysburg. Within an hour the young newlywed would be leading his men toward a developing fight, several miles to the north and west, his pulse quickening as the sounds of battle became less distant with each step.

[1]

Gilbert Arnold Dickey was born on February 18, 1843, in Marshall, Michigan, one of ultimately seven children born to Charles and Mary Wakeman Dickey. His ancestry was Scotch-Irish and, until recently, his family were New Englanders; his mom and dad–born respectively in Massachusetts and New Hampshire–had emigrated to Michigan just seven years earlier, in 1836, settling in Marshall, which is near Battle Creek, and about 100 miles west of Detroit. Once he arrived, it was not long before Charles Dickey–Gilbert’s father–became a leading member of his adopted community. With a background in manufacturing and in business, Charles Dickey, in 1842, was elected sheriff of Calhoun County, a position he held for the next four years. Entering into politics, he served also as mayor of Marshall and, in 1848, won election to the Michigan State Senate. He was later elected to the Michigan House of Representatives where he served as Speak Pro Tempore and, in early 1861, he was appointed a U.S. Marshal by newly-inaugurated President Abraham Lincoln. Gilbert Dickey’s father was certainly an influential part of his life; sadly, though, he would lose his mother Mary at an early age. She died the day after Christmas in 1852 at age 40, when Gilbert was only nine years old.[2]

A bright and energetic young man, Gilbert Dickey at around age 14 enrolled as one of the very first students in the recently established Michigan State Agricultural College, which today is Michigan State University. One of only seven students in the college’s Class of ’61, Dickey was engaged in his studies at the college when civil war erupted that spring. Michiganders responded eagerly to the crisis with thousands of its sons marching off in answer to Lincoln’s call-to-arms. Caught up in the patriotic surge that swept the nation following news of Fort Sumter’s fall, Dickey and his classmates also sought to contribute something to the war effort.

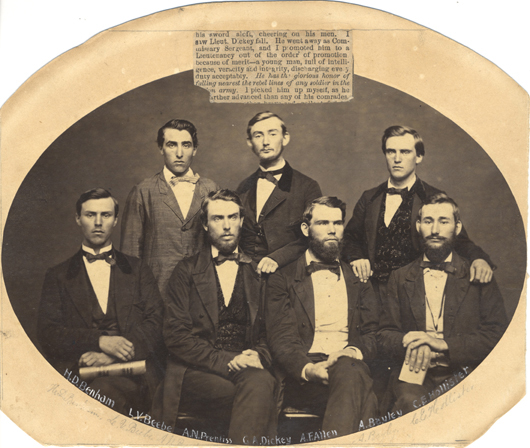

Photograph of the Michigan State Agricultural College Class of 1861; Gilbert Dickey is Standing, Center.

[Courtesy of Michigan State University Archives and Historical Collection]

They set about organizing a grand and patriotic Fourth of July Celebration to take place on the college grounds. Bells would be rung, music performed, fireworks set off, and several salutes fired. Prayers would be delivered and the Declaration of Independence would be read aloud. There would also be an oration, delivered, it was determined, by Gilbert Arnold Dickey. As it turned out, the event–this celebration of the United States while in the midst of its greatest trial–was a “magnificent affair,” attended, reportedly, by nearly 5,000 people. Perhaps inheriting the gift of oratory from his father–the one time Speaker Pro Tem of the Michigan House of Representatives–Gilbert Dickey shined. “The Oration was very creditable to Mr. Dickey,” reported the

Lansing State Republican. “It was terse, logical and well written. The subject–Patriotism, was well treated and the duties which patriotism enjoins set in a clear light.”

[3]

But no matter how stirring, words alone cannot win wars. The nation needed soldiers; it was one of those important duties “patriotism enjoins.”

Gilbert Dickey and his six classmates in the Michigan State Agricultural College were scheduled to graduate that fall, with commencement to take place in November. However, to help meet the exigencies of the day and likely at their urging, the college allowed these men special exemptions to depart early.[4] A company of engineers was being formed in nearby Battle Creek and it would appear Dickey and his classmates were eager to enlist.

In September 1861, Edwin P. Howland set about raising and organizing a company of engineers, which he dubbed the “Battle Creek Engineer Corps,” but which was also Howland’s Independent Company, Michigan Volunteers. Howland was able to gather fifty-eight recruits, including Gilbert Dickey and five of his six classmates. Enlisting on September 16, 1861, Dickey set off for war. Howland’s engineer company departed for St. Louis, where it was mustered into Federal service on October 9. This was to be a three-years’ unit, with the men agreeing to serve “for three years or the course of the war,” whichever should come first. However, Howland’s experiment with his engineering company proved to be short-lived. Taking command of the Department of Missouri in late 1861, Major General Henry Halleck deemed that the “Battle Creek Engineering Corps” was an irregular unit, which did not meet Federal standards. Learning of Halleck’s decision, the soldiers of Howland’s company took a vote and decided to disband. Receiving pay for their short time in uniform, the Battle Creek engineers were mustered out of service on January 8, 1862, and returned home.[5]

Gilbert Dickey returned to his home in Marshall. Several of his classmates immediately decided to re-enlist into other regiments but he would take some time before doing so. There were other thoughts occupying his mind just then; one of them being Miss Rosetta Beecher. It is not known when they met or how long they knew one another but on July 1, 1862, the two were married. Thoughts of a family, however, were put on hold, for the call of duty still pulled strongly on Gilbert.

Already fifteen months in and the war still bloodily dragged on and on, much longer than many anticipated at its outset. Lincoln needed more men and throughout the spring and into the summer of 1862 he contemplated making another call for volunteers. His mind made up, Lincoln issued a statement to the Northern governors. It read, in part, “I have decided to call into the service an additional force of 300,000 men. I suggest and recommend that the troops should be chiefly on infantry. . . .I trust that they may be enrolled without delay, so as to bring this unnecessary and injurious civil war to a speedy and satisfactory conclusion.”[6] Quotas for volunteers were assigned to each state. The date of this fateful directive written by President Lincoln in the White House was, coincidentally, July 1, 1862, the very same day, in faraway Marshall, Michigan, that Gilbert Dickey and Rosetta Beecher were married.

In response to Lincoln’s call, Republican Governor Austin Blair set about to meet Michigan’s quota of at least six new infantry regiments. Once more, through town and township, city and sparse settlement, the call for men sounded, and, in Marshall, Gilbert Dickey answered. Several regiments were being raised and organized in Detroit and there Dickey traveled. On August 12, Dickey signed on to serve, enlisting into what would become Company E of Michigan’s Twenty-fourth Regiment of Volunteer Infantry. Dickey was soon made the regiment’s Commissary Sergeant, a post he held until January 27, 1863, when he was made the regiment’s sergeant-major. Trusting such important assignments to a man as young as Dickey (he wouldn’t turn 20 until February 1863) speaks volumes about his leadership, intelligence, skill, and ability, as well as to the trust his superior officers had in him.[7]

Its ten companies fully raised and organized, the 24th Michigan Infantry set off for the seat of war., but whereas most of Michigan’s regiments would serve in the war’s Western Theater, the 24th instead headed east, traveling to Washington, D.C. where it was to link up with the Army of the Potomac. Noting its arrival, Brigadier General John Gibbon, a no-nonsense professional soldier who commanded the Army of the Potomac’s famed “Iron Brigade of the West,” made a special request for the recently arrived Michiganders to join his veteran organization. Gibbon’s Brigade–the only all-western brigade in this largely eastern army, and consisting of the 2nd, 6th, and 7th Wisconsin and 19th Indiana–had already become revered, earning its fitting sobriquet for their heroics in action Brawner’s Farm, South Mountain, and most recently at Antietam. Upon all of these fields, the Iron Brigade suffered appalling losses. Gibbon hoped to add the brand new 24th Michigan regiment to bolster his fearfully depleted command while at the same time maintaining its distinctive all-Western composition. In October , Gibbon’s request was approved and Sgt. Dickey and the men of the 24th Michigan now found itself apart of one of the hardest-hitting units in any army of this war. To the seasoned, veteran soldiers from Wisconsin and Indiana, these greenhorns from Michigan would have much to prove. And this the Michiganders did during the regiment’s first test in battle, which came at Fredericksburg in December 1862. After some initial unease while under artillery fire for the first time, the 24th Michigan, under its brave and highly competent commander Henry Morrow, charged a woodlot and cleared it of Confederate troops. Their actions at Fredericksburg, where the 24th would suffer its first battlefield fatalities, earned the respect of many of their comrades in Iron Brigade but if there was still any lingering doubt as to the fighting ability or prowess of these men from Michigan, they would forever be put to rest following the Battle of Gettysburg.

Disease, discharges, desertions, and the relatively few casualties sustained during the Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville Campaigns had reduced the number of men in the 24th by nearly fifty percent so that, on the eve of the Battle of Gettysburg, there were 496 officers and men in the regiment, roughly half the number that had departed Detroit just eleven months earlier in late August 1862. And now, on the morning of July 1, 1863, with the temperature rising and the morning dew quickly evaporating, these 496 men made their way north along the Emmitsburg Road, toward Gettysburg and the escalating sound of battle emanating off to the northwest. Within the advancing column was Gilbert Dickey, who, in March, had been promoted from the regiment’s sergeant-major to 2nd Lieutenant of Company G. Whether he rode along on horseback or marched on foot aside of his men is not known. But it was probably certain that on that Wednesday morning, July 1, 1863, Lt. Gilbert Dickey wished that he was rather at home with his wife Rosetta to celebrate their first wedding anniversary, instead of in far off south central Pennsylvania, advancing to the sounds of the guns.

Off to the northwest, Union Cavalrymen under the indomitable John Buford were being hard-pressed by advancing Confederate soldiers from Alabama, Tennessee, Mississippi, and North Carolina. The first shots of the Battle of Gettysburg had been fired several hours earlier, further to the west, but now the battle inched its way closer Gettysburg. Buford’s outnumbered horsemen were holding desperately atop the ridgelines immediately west of town, hoping to delay the thundering gray-and-butternut columns long enough for infantry to arrive. As Buford’s men gave ground stubbornly on either side of the Chambersburg Pike, that much-needed infantry support was just then hastening way up the Emmitsburg Road from the south.

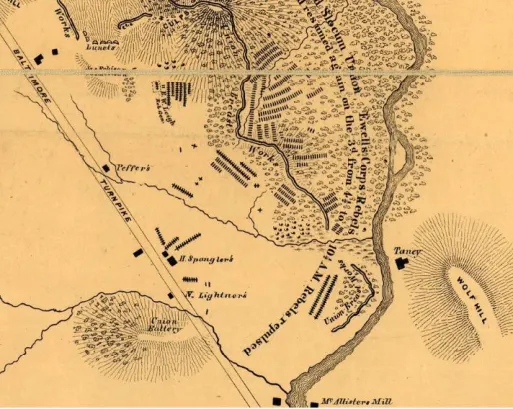

The infantry advancing to Buford’s support was the First Corps, commanded by Major General John Reynolds. At the head of the First Corps marched its First Division, commanded by General James Wadsworth. Wadsworth had two brigades under his command; one, under Lysander Cutler, led the way toward the developing fight. The other, the famed and feared Iron Brigade, advanced behind Cutler’s men. General Solomon Meredith now commanded the Iron Brigade–Gibbon having by this time been promoted to divisional command in the army’s Second Corps. Colonel Henry Morrow, however, continued to lead the 24th Michigan as it made its way forward that Wednesday morning. 2nd Lt. Gilbert Dickey, in Company G of the 24th Michigan, was but one of the more than 12,000 First Corps soldiers making their way toward the fight.

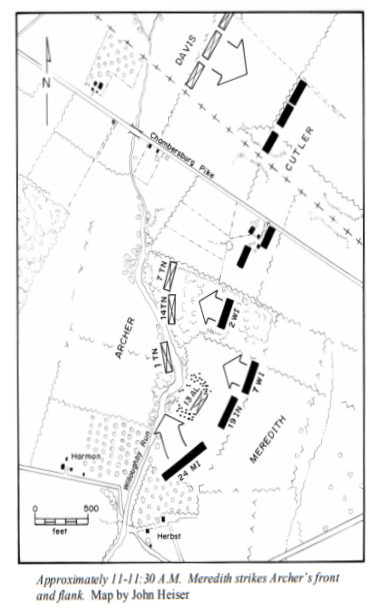

And they would arrive none too soon. First to arrive was Cutler’s brigade, which Reynolds positioned astride the Chambersburg Pike, with three regiments stretching north to contend with Joe Davis’s advancing Confederate brigade and two regiments posted south of the Pike to deal with another approaching Confederate brigade, the hard-fighting Tennesseans and Alabamians under General James Archer. Both Archer and Davis’s Brigades belonged to Harry Heth’s division; Heth had been instructed that morning to march toward Gettysburg to determine the size of a Union force reported to have been in the area. Still, he was to avoid battle. With the arrival of the Union First Corps, however, the battle only intensified. Heth’s ranks were slowed but still they had the advantage in that their lines far outflanked Cutler’s men on both sides of the Chambersburg Pike. After positioning Cutler’s men, Reynolds galloped southward to the eastern edge of an eighteen acre woodlot owned by local farmer John Herbst. Through the trees, the First Corps commander could discern soldiers in gray and butternut advancing from the west. These were soldiers from Archer’s brigade who were just then threatening the left flank of Cutler’s brigade, positioned north of the woodlot. At this critical moment, however, additional help arrived.

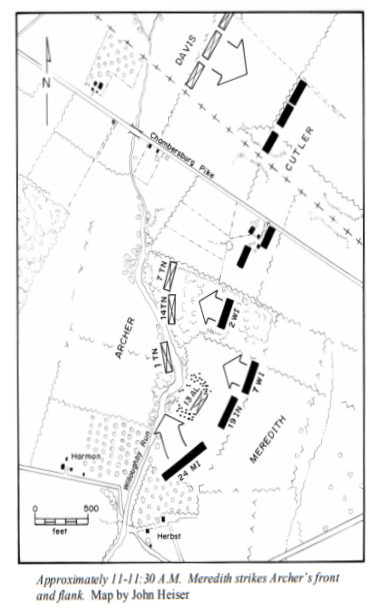

Turning left off the Emmitsburg Road near the Nicholas Codori house and barn and advancing cross-lots to the northwest, the soldiers of Solomon Meredith’s Iron Brigade arrived on the field, its regiments entering the fray piecemeal. The 2nd Wisconsin, at the head of the column went in first and there, in John Herbst’s woodlot, they engaged in a savage fight with the 7th and 14th Tennessee of Archer’s Brigade. Musketry roared as the two sides came to blows. Among those struck down in this exchange of gunfire was First Corps commander John Reynolds. Urging the Badger State soldiers forward, Reynolds was struck in the back of the head and instantly killed.[8]

The rest of the Iron Brigade soon entered the fight. The 7th Wisconsin moved forward to support the bloodied 2nd still slugging it out in the woodlot, with the 19th Indiana advancing to the left of the 7th. To the left of the 19th Indiana came Colonel Henry Morrow’s 24th Michigan. (The remaining regiment of the Iron Brigade–the 6th Wisconsin–was held back as a reserve at the Lutheran Seminary).

The 24th moved forward at the double-quick, down the slope of Seminary Ridge then up and over the crest of McPherson’s Ridge, just to the south of Herbst’s Woods. They charged into the fight with unloaded muskets for there was no time to spare. As it turned out, the 24th had fortuitously arrived on the field squarely on Archer’s exposed right flank, even as their comrades in the Iron Brigade hit Archer’s men head-on. Soldiers of the 13th Alabama, on the right of Archer’s line, delivered several volleys into the hard-charging Michiganders, inflicting the regiment’s first losses of the day. Among the fallen was Abel Peck of Dickey’s Company G, who carried flag of the 24th, shot and instantly killed; he would be the first of seven men to fall that day bearing aloft the regiment’s flag.

Despite the losses, the onslaught of the Iron Brigade overwhelmed Archer’s line. Archer’s men raced rearward in full retreat, with the soldiers of the Iron Brigade on their heels, flush with victory. Down the western slope of McPherson’s Ridge, the men from

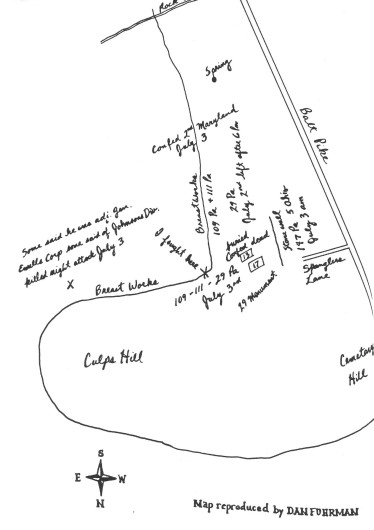

The Monument of the 24th Michigan Infantry in Herbst/McPherson’s Woods

Michigan, Indiana, and Wisconsin, swept through the undergrowth that lined the banks of the swift-flowing Willoughby Run. Splashing across, the Iron Brigade continued its pursuit of Archer’s men until orders finally arrived to halt. Archer lost 1/3 of his command; he himself was among the captured. The first Confederate advance toward Gettysburg had been repulsed but the battle was still only getting started.

2nd Lieutenant Gilbert Dickey had made it through this initial encounter with Archer’s men. After receiving orders to halt, Dickey and the men of the 24th Michigan splashed back across Willoughby Run and labored up the creek’s steep eastern bank. There, atop this rise of ground in Herbst Woods, the Iron Brigade redeployed, facing west to meet any more Confederate challenges. On the right of the Iron Brigade’s new line was the 7th Wisconsin, followed by the 2nd Wisconsin. Forming up to the left of the 2nd was the 24th Michigan, with Lt. Dickey no doubt scrutinizing the ground. Finally, to the left of the Michigan men went the 19th Indiana, holding the brigade’s left flank.

There was a little bit of a respite now in the day’s action as the First Corps readied for another attack. Shells fired by Confederate artillery batteries to the west exploded amongst the treetops overhead while, to the front, a sometimes brisk skirmish fire continued unabated. During this so-called “lull” in the fighting, however, Confederate officers made plans to renew the offensive against the First Corps.

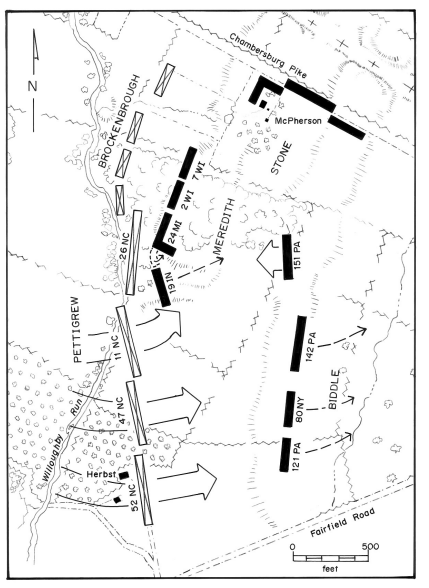

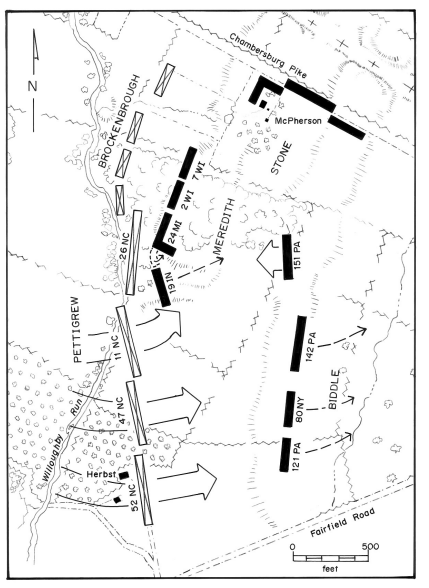

A mile to the north of Herbst Woods and certainly out of view of the Michigan men who were now laying down in the woodlot another division of Confederate infantry, some 8,000 men under Robert Rodes, arrived on an open hilltop known as Oak Hill and squarely opposite the right flank of the First Corps, which had also been repositioned north of the Chambersburg Pike. Rodes’s superior–Richard Ewell–was there also, and although he too was told to avoid battle, the right flank of the First Corps was just too tempting a target to resist. Rodes launched a series of attacks from that hilltop, each repulsed with heavy loss. Meanwhile, atop Herr’s Ridge to the west, Harry Heth watched as Rodes’s lines were turned back. He readied his own division for a renewed attack, to strike the First Corps head-on while Rodes continued to hammer their right flank. In line of battle south of the Chambersburg Pike, Heth positioned the Virginians of John Brockenbrough’s Brigade. Next to Brockenbrough and continuing the line south went the 2,000 North Carolinians of Johnson Pettigrew’s Brigade, while the remaining soldiers of Archer’s Brigade formed up to the right of Pettigrew. Heth now had over 4,000 men in position. All he needed was the order to attack.

Confederate army commander Robert E. Lee had by now arrived on Herr’s Ridge, no doubt greatly perturbed that several of his subordinates had violated his instructions to avoid battle that morning. Heth pressed him with requests to renew his attack from the west. At first Lee rejected Heth’s pleas but, at around 2:30, and sensing an opportunity to inflict damage on a part of the Union army, he changed his mind and directed Heth forward. Heth’s line swept down Herr’s Ridge, across the Harmon Farm, and directly toward the Union soldiers positioned to their front on McPherson’s Ridge and in Herbst’s Woods. 2nd Lieutenant Gilbert Dickey watched through the trees as this massive gray wave approached. Advancing straight at him and the men from Michigan were the 840 men of the 26th North Carolina Infantry. All along the line, the men of the Iron Brigade braced for impact as the Confederate line got closer and closer with each passing moment, their piercing “rebel yell” heard even above the booming of cannons.

Colonel Morrow of the 24th Michigan later remembered that the “enemy advanced in two lines of battle, their right extending beyond and overlapping our left.” He instructed his men “to withhold their fire until the enemy should come within short range of our guns.” They waited until the Confederates were within just 80 yards they opened a devastating fire. The North Carolinians were in the midst of crossing Willoughby Run and negotiating their way up through the briars and thickets that lined its banks when the Michiganders opened this heavy fire. Still, wrote Colonel Morrow, “Their advance was not checked, and they came on with rapid strides, yelling like demons.”[9]

In Herbst’s Woods, the Iron Brigade found itself isolated, outflanked, and outnumbered. The 26th North Carolina soon returned fire with the 24th Michigan at nearly a points’ blank range, by some estimates only 20 to 40 yards apart. Bullets tore through the ranks, with both the 26th North Carolina and the 24th Michigan suffering fearful losses. To the left of rapidly thinning ranks of the 24th Michigan, the 19th Indiana was being hammered on its front and on its exposed left flank by the oversized 11th North Carolina Infantry. There was little the Hoosiers could do. After stubbornly and desperately holding on as long as possible–maybe ten or fifteen minutes–the 19th Indiana was forced back. This, in turn, exposed the left flank of the 24th Michigan. To meet the new threat presented by the 11th North Carolina Colonel Morrow attempted to swing back, or “refuse,” the left of his regiment.

Holding the left of the 24th Michigan’s line were Company D and Gilbert Dickey’s Company G. When Colonel Morrow’s orders arrived to refuse their line in order to face the 11th North Carolina head-on, these two companies were already under a heavy fire making such a maneuver in the face of this fire a difficult thing to do. The attempt was made but, as Colonel Morrow later reported, during the execution of this movement, “the enemy advanced in such force as to compel me to fall back.” Orders were shouted and the 24th Michigan fell back, slowly, stubbornly, turning several times to fire into the surging gray lines.

Left behind, however, in that woodlot and atop the ridge overlooking Wiloughby Run was the lifeless body of 2nd Lieutenant Gilbert Arnold Dickey. The twenty-year old officer, a young man who, to Colonel Morrow held such “great promise,” was shot and killed while he attempted to turn his men to face south; he would be the first, but certainly not the last, commissioned officer in the 24th Michigan to die that day. Victorious North Carolinians, “yelling like demons,” raced past Dickey’s corpse as they continued to drive the ever-decreasing remnants of the 24th Michigan back through those trees in Herbst Woods, which was by now almost entirely enshrouded in thick, sulfurous smoke.

Heth’s second attack that day broke the Union line on McPherson’s Ridge. A follow-up assault launched by Dorsey Pender’s fresh Confederate division, coupled with the relentless attacks of Rodes’s Division to the north, would drive what remained of the Union First Corps from the fields west and north of Gettysburg, and back through the town itself, ultimately to the high ground known as Cemetery Hill where the Union forces rallied. There, the shattered remains of the Iron Brigade gathered. Casualties within the brigade were so severe that, for all intents and purposes, the organization would almost cease to exist. Of the total 1,885 men in the brigade, more than 1,200 became casualties at the Battle of Gettysburg, the vast majority of these losses occurring in and around John Herbst’s woodlot on July 1, 1863. In the 24th Michigan, 363 of the regiment’s 496 officers and men were killed, wounded, or captured, a staggering 73% casualty rate. Theirs was the sad distinction of losing the largest number of casualties of any regiment in the Army of the Potomac at Gettysburg.

During the ensuing two days–on July 2 and 3, 1863–Robert E. Lee attempted but in the end failed to force the Army of the Potomac from the high ground south of Gettysburg–Little Round Top, Cemetery Hill, Cemetery Ridge, and Culp’s Hill. After Lee’s army retreated from the blood-soaked fields around Gettysburg, the remains of the fallen were buried in hastily dug battlefield graves. While the sights–and smells–were appalling all across the battlefield in the immediate aftermath of the battle, this was especially the case on the fields of the First Day’s fight. There the dead had remained unburied for days, decomposing in the July heat. First Corps artillery chief, Charles Wainwright, wrote that the First Corps dead “presented a ghastly sight, being swollen almost to the bursting of their clothes, and the faces perfectly black.”[10] Even so, burial parties did their best to identify the remains of the fallen. It was the least that could be done for those who had given their lives so that the nation could live. Among the identified remains were those of Lieutenant Gilbert Dickey, who was laid to rest near where he fell in Hersbt Woods.

Word of Gilbert Dickey’s death arrived in his hometown of Marshall, Michigan, soon after the battle, for, just one week later, the slain lieutenant’s father, Charles Dickey, arrived in Gettysburg with several others from the Detroit Board of Trade. Amongst the many graves that now marked Herbst Woods, a grief-stricken Charles Dickey discovered that of his son. Rather than arrange for the removal of his son’s remains for reburial at home in Michigan, however, Charles Dickey decided to let them rest where they were; there, where he fell, surrounded by others who died in defense of the Union. Later, Dickey’s body would be removed and reburied in the Soldiers’ National Cemetery.

The Grave of Gilbert Dickey in the Soldiers’ National Cemetery, with the incorrect inscription of “S. Cavalry.”

In a cruel twist of fate and sad coincidence, Rosetta Beecher Dickey lost her husband Gilbert on their First Wedding Anniversary. It is not known when the two had last seen one another but it must have been some months before, in either late April or early May 1863, when Gilbert likely received a furlough to visit home, for, whether he knew it or had yet to find out when he went into battle at Gettysburg on July 1, 1863, Rosetta Dickey was two months pregnant. Gilbert was due to become a father sometime in early February 1864.

Rosetta Dickey applied for a pension in the fall of 1863, before she delivered her baby and thus, unfortunately, the pension records do not include the baby’s name or even its date of birth. She would, however, receive a pension of $15.00 a month. Rosetta Beecher Dickey never remarried and remained a Civil War soldier’s widow for the next fifty-eight years. She passed away in the summer of 1921 and was buried in the Riverside Cemetery in Kalamazoo, Michigan. More than 500 miles away from her final resting place lie the remains of her husband Gilbert, at Gravesite 7, Section A, in the Michigan Plot at the Soldiers’ National Cemetery in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania.

-Ranger John Hoptak

Gettysburg National Military Park

[1] Dickey, Rosetta Beecher, Case Files of Approved Pension Applications of Widows and Other Veterans of the Army and Navy Who Served Mainly in the Civil War and the War With Spain, compiled 1861 – 1934; roll WC13071-Dickey-Gilbert-A Department of Veterans Affairs, Record Group 15; National Archives, Washington, D.C.

[2] American biographical history of eminent and self-made men … Michigan volume. Barnard, F. A., Western Biographical Publishing Company (Cincinnati, Ohio) Cincinnati: Western biographical publishing co., 1878, pages 455-456.

[3] Lansing State Republican, Wednesday, June 12, 1861, page 3; Lansing State Republican, Wednesday, July 10, 1861, page 3.

[4] https://onthebanks.msu.edu/Object/162-565-3078/class-of-1861-portrait/, accessed March 30, 2020.

[5] http://www.migenweb.org/michiganinthewar/engineers/howland.htm, accessed March 27, 2020.

[6] The Papers and Writings of Abraham Lincoln, Volume 2: 1860-1865, printed by CreateSpace, North Charleston, SC;, page 163.

[7] For a regimental history of the 24th Michigan, see Curtis, O.B. History of the Twenty-fourth Michigan of the Iron Brigade, Known as the Detroit and Wayne County Regiment, Detroit, MI: Winn & Hammond, 1891.

[8] For an excellent account of the actions of the Iron Brigade on July 1, 1863, see Hartwig, D. Scott, “I Have Never Seen the Like Before,” in This Has Been A Terrible Ordeal: The Gettysburg Campaign and First Day of Battle, Papers of the Tenth Gettysburg National Military Park Seminar, 2005; pages 155-196.

[9] Colonel Morrow’s Report on the Battle of Gettysburg, in OFFICIAL RECORDS: Series 1, vol 27, Part 1 (Gettysburg Campaign) No. 33. pp. 267-273

[10] Quoted in Hartwig, “I Have Never Seen the Like Before,” 188.

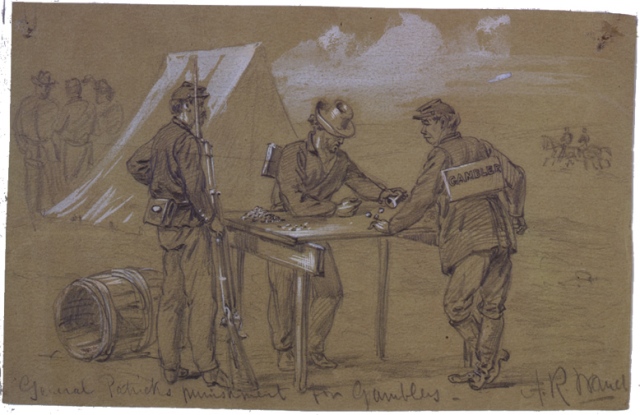

In a segment entitled, The Modern Case of John Brown,” Ashe invited Dr. Lyon Gardiner Tyler (descendant of President John Tyler) to write “The parallel afforded by the cases of [Nicola]Sacco and [Bartolomeo] Vanzetti to that of John Brown is too striking not to be noticed by the historian.”

In a segment entitled, The Modern Case of John Brown,” Ashe invited Dr. Lyon Gardiner Tyler (descendant of President John Tyler) to write “The parallel afforded by the cases of [Nicola]Sacco and [Bartolomeo] Vanzetti to that of John Brown is too striking not to be noticed by the historian.”

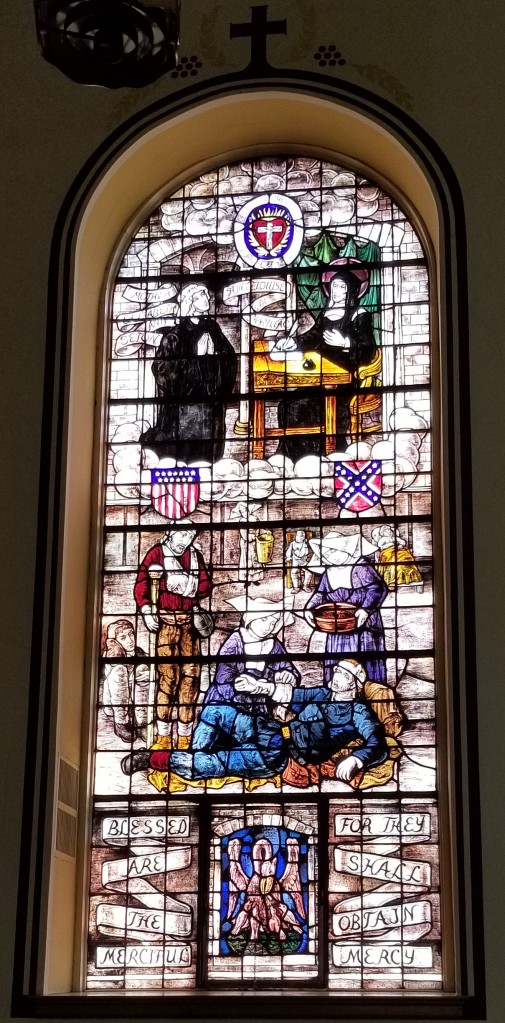

Well-organized, and provided with five maps, Bigelow’s account is concise, primarily (and perhaps expectedly) through the viewpoint of the artillery service. Broken into three parts, the first portion deals with an overview of the Second Day’s fight, and the role of the forces of the ‘Long Arm’ in their proper supporting role in the Third Corps debacle. The critical role of supporting infantry, either by its presence or absence, is noted; but not indulged. Relevant elements from various Official Records reports (noted as Rebellion Record) are cited. One of those marvelous tidbits of precision reading is to be found in this segment of the book. For many, there has always existed the “Who was right- Meade or Sickles?” question. Should the Third Corps have been posted to the orchard? If so, it was bound to require artillery support. Take in General Hunt’s perspective – what he does, and does not say. (p. 36)

Well-organized, and provided with five maps, Bigelow’s account is concise, primarily (and perhaps expectedly) through the viewpoint of the artillery service. Broken into three parts, the first portion deals with an overview of the Second Day’s fight, and the role of the forces of the ‘Long Arm’ in their proper supporting role in the Third Corps debacle. The critical role of supporting infantry, either by its presence or absence, is noted; but not indulged. Relevant elements from various Official Records reports (noted as Rebellion Record) are cited. One of those marvelous tidbits of precision reading is to be found in this segment of the book. For many, there has always existed the “Who was right- Meade or Sickles?” question. Should the Third Corps have been posted to the orchard? If so, it was bound to require artillery support. Take in General Hunt’s perspective – what he does, and does not say. (p. 36)

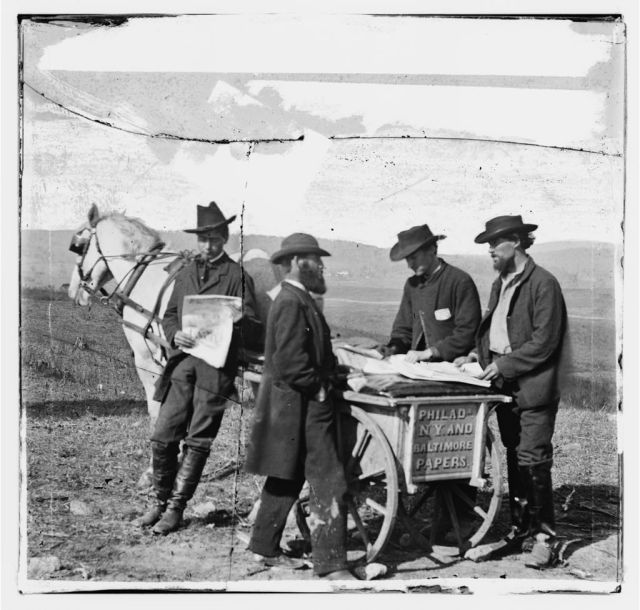

In the first six months of printing the company sold sixty-five thousand copies, no doubt more than a handful making their way into the hands of new soldiers. Dime novels were, as the name suggests, inexpensive and they could be easily carried by men on the march. Once a soldier was done with it, the book could be traded for another with a comrade who may be carrying a different title.

In the first six months of printing the company sold sixty-five thousand copies, no doubt more than a handful making their way into the hands of new soldiers. Dime novels were, as the name suggests, inexpensive and they could be easily carried by men on the march. Once a soldier was done with it, the book could be traded for another with a comrade who may be carrying a different title.