CCC enrollees arriving by train for M.P.-2, McMillan Woods, Gettysburg Train Station, ca. 1935.

In the summer of 1933, some seventy years after generals Robert E. Lee and George G. Meade led their armies to Gettysburg, a new army arrived. Composed of young men, this new volunteer army was unlike any one created by the United States government before. Instead of shouldering rifles, these volunteers were armed with shovels, saws, and pickaxes. Rather than learn about military strategy and tactics, these men were taught about the conservation of the nation’s natural resources. Their enemy was not some foreign power. The enemy was an economic depression that had, at its height, put an estimated fifteen million Americans out of work and denied them the opportunity to support their communities, families, and themselves. This new army was called the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), and Gettysburg was but one battlefield in the campaign to put Americans back to work.

In his First Inaugural Address on March 4, 1933, President Franklin D. Roosevelt pledged to put Americans to work, but just as important, he laid out his plans of attack. “Our greatest primary task,” Roosevelt acknowledged, “is to put people to work.”[1] For those Americans who had lost hope for economic relief, Roosevelt reminded them that the problem was not “unsolvable” if faced “wisely and courageously.”[2] Unemployment relief could “be accomplished in part by direct recruiting by the Government itself,” Roosevelt insisted, and “treating the task as we would treat the emergency of a war…”[3] Roosevelt then mentioned a secondary goal, which was to accomplish “greatly needed projects to stimulate and reorganize the use of our natural resources.”[4] Roosevelt wanted to use public lands, such as the Gettysburg battlefield, to help a crumbling nation. Twenty-seven days after his Inaugural Address, Roosevelt signed the Unemployment Relief Act, which established the CCC, one of Roosevelt’s most successful New Deal programs.[5]

Within the first year of its existence, Roosevelt allowed for 250,000 recruits to enroll in the Emergency Conservation Work program, as the CCC was first known. An additional 25,000 local experienced men, or LEM’s, were accepted to teach the unskilled enrollees the various trades to accomplish their work assignments. Another 25,000 military veterans who had been unable to find employment were also accepted. Enrollment was further expanded in July with the acceptance of 12,000 American Indians. These approximately 300,000 enrollees, organized into companies of about 200 men each, were placed in 1,468 camps located in every state across the country. In Roosevelt’s opinion, the mobilization of the CCC “was the most rapid large-scale mobilization of men” in the country’s peace-time history.[6]

The first wave of recruits had to meet certain criteria in order to join the CCC. Recruits had to be unemployed, unmarried, between the ages of eighteen and twenty-five, and willing to send $25.00 of their $30.00 monthly allowance home to their families. Those who enrolled had to serve a minimum six month enlistment, but they could continue serving for up to two years if they were unable to find employment elsewhere.[7] Recruits also had to be male. While women filled supportive roles for the CCC in some instances, none became enrollees.

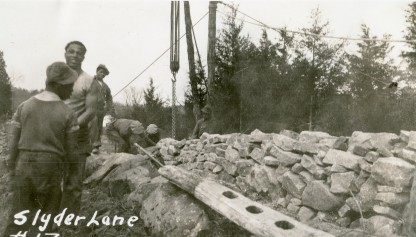

Restoring a stone wall along Slyder Lane, ca. 1937.

The CCC had a profound impact on the United States during its nine year existence – politically, economically, socially, and of course, environmentally. The program nonetheless maintained various societal norms that undercut its own potential, restricted the nation’s economic recovery, and reminded a class of American citizens of their status in society. The CCC perpetuated racial inequalities principally toward African Americans by limiting their enrollment by using a system of quotas based on state populations, limiting the rise of African Americans to leadership roles, and establishing segregated camps.

Of the approximately 2.5 million enrollees that served in the CCC from 1933 to 1942, about 250,000 were African American.[8] These figures would have been higher if the CCC administration and Advisory Council had not confined African American enrollment from exceeding ten percent of the program’s national total.[9] Even as various New Deal programs were implemented, the number of African Americans receiving relief increased from 1933 to 1935.[10] If volunteering for the CCC was harder for black youth than white, rising to a leadership position within the CCC was even more difficult. In an organizational structure similar to that of the United States Colored Troops that fought in the Civil War, it was customary for white officers to command black enrollees. Resistance by the U.S. Army, potential negative publicity of the CCC for allowing black leadership, and minimal interest and support in the matter by the White House and politicians denied aspiring black enrollees a chance at advancement.[11] Those who were appointed to leadership roles would serve in black camps only. Lastly, inequality existed in the form of segregated camps, which were established with little regard because of the “separate but equal” philosophy that existed across the country.

The arrival of the relief program at Gettysburg coincided with that of the National Park Service. Prior to the summer of 1933 the battlefield had been maintained by the United States War Department. James R. McConaghie, the first NPS superintendent at Gettysburg, had requested 100 enrollees to provide various improvements to the battlefield. McConaghie’s request was approved, and the first company – Company 385-C – arrived in June, with three white officers and 180 African American enrollees.[12]

Gettysburg provided an appropriate backdrop for black enrollees. Those American youths were stationed on a battlefield from a war fought to preserve the Union and end the enslavement of African Americans, but one that ultimately fell short from reaffirming the ideal that “all men are created equal.” The enrollee’s surroundings on that “great battle-field of that war” would have reminded them of what the Civil War failed to achieve just as much as what was accomplished. Many must have wondered whether or not President Abraham Lincoln’s vision for “a new birth of freedom” had yet been realized.

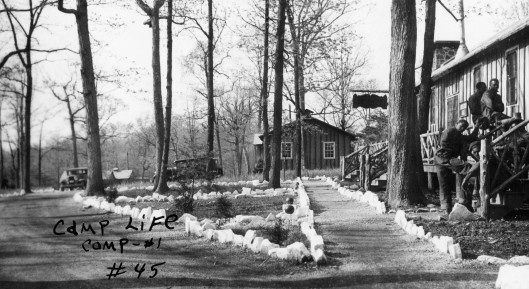

Park Superintendent James McConaghie with camp officers at M.P.-1 in Pitzer Woods, ca. 1934.

It was, perhaps, fitting that Company 385-C was detailed to Gettysburg, especially since it had been organized at Fort George G. Meade, in Maryland, on June 2, 1933.[13] After its organization, the company was transported by rail to Gettysburg, then transferred by bus to their camp, called MP-1, or what the enrollees would soon call Camp Renaissance.[14] MP-1 was located southwest of the town in Pitzer’s Woods on Seminary Ridge, an area occupied by the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia during the July battle. MP-1 was in operation until April 12, 1937 when it was closed due to budgetary cuts.

The residents of Gettysburg were fortunate to have enrollees stationed nearby. The town would benefit from the variety of projects carried out by the enrollees, which would drive tourism and enhance the visitor experience. More immediately, however, the local economy could expect a jump-start from the money enrollees were expected to spend at various businesses. Yet there was a reluctance to have black enrollees living and working nearby. As a preemptive measure, the Gettysburg Times told its readers that the arrival of the first black enrollees was only temporary, and that this contingent had been sent to Gettysburg to establish a camp for a forthcoming white company.[15] This news also made the area’s representative in Washington, D.C. to take action. Congressman Harry L. Haines was either personally unhappy about a black company at Gettysburg, or he received a significant response from his constituents who were unhappy as well. Haines wrote to Robert Fechner, the director of the CCC, asking that Company 385-C be sent to a more remote area, but the request was ineffectual.[16] Despite this initial hesitancy, it appears that the town came to value the CCC camps on the battlefield, even if they were black camps. The community planned to send a delegation to Washington to persuade Director Fechner to keep both MP-1 and MP-2 open when it was learned that one camp would be abandoned.[17]

M.P.-1 buildings in Pitzer Woods, ca. 1934.

The work to be performed by Company 385-C was chosen specifically by Superintendent McConaghie. Projects ranged from transplanting and pruning trees, cutting and hauling wood, removing stumps, to lawn maintenance and other projects.[18] New projects sometimes popped up unexpectedly and added to the workload. Such was the case on July 2, 1933 when a twister roared through MP-1 and went tearing toward Little Round Top and Big Round Top, leaving debris of every description in its wake. MP-1 was devastated. The forty-five tents used to house the officers and enrollees were all blown down and various camp items were scattered about. It seemed as though Little Round Top and Big Round Top received the heaviest blow, however. Some 275 trees were knocked over or snapped by the twister’s strong winds.[19]

Enrollees resetting the gravestones in the Solders’ National Cemetery, ca. 1934.

Other work assignments concealed hidden dangers beyond those that are typical to manual labor. While enrollees were working near the National Cemetery in 1934 two “grapeshell bombs” were unearthed. The enrollees believed the artillery rounds were duds and therefore safe to handle. The projectiles were taken back to MP-1 and placed inside the camp headquarters as gifts to Captain Francis J. Moran. Moran, a World War I combat veteran, realized that the projectiles were actually live! He quickly ordered that they be taken to an open field at once. Moran had the Civil War projectiles placed side-by-side, braced on either side with logs, and had two sticks of dynamite placed underneath. On Moran’s command the seventy year old artillery rounds were exploded, thus preventing any terrible accident from happening to any person.[20]

Aside from its regular duties, Company 385-C responded to various emergencies within the state. When Pennsylvania’s rivers and streams flooded in 1936 Company 385-C sent a three truck convoy with food and clothing to those citizens impacted by the floods.[21] The enrollees also fought to contain several forest fires. In May 1936, Superintendent McConaghie led sixty enrollees southwest of Gettysburg to McKee’s Knob near Fairfield, where they fought for six hours to contain a fire begun by embers from a nearby barn that had caught fire.[22] Fortunately, no human lives were lost.

Enrollees painting the iron picket fence separating Soldiers’ National Cemetery and Evergreen Cemetery, ca. 1936-1939.

The work was tough, but it filled an important void in the lives of the enrollees. President Roosevelt was aware of the tangible gains the United States could reap with the CCC at work, but he also understood the intangible gains that could be had by placing the unemployed in “healthful surroundings.”[23] In a message delivered to members of the Congress, Roosevelt wrote that “More important, however, than material gains will be the moral and spiritual value of such work…We can eliminate to some extent at least the threat that enforced idleness brings to spiritual and moral stability.”[24] The CCC was not only designed to relieve a nation, it was designed to rescue the souls of young Americans from idleness.

The enrollees of Company 385-C, along with enrollees throughout the CCC, were able to keep themselves busy outside of their work assignments. The CCC facilitated opportunities for personal exploration and growth that a generation of American youths may not have had otherwise. Numerous sports activities were available to the enrollees, including baseball, boxing, quoits, basketball, volleyball, and ping pong. The company even formed a drum and bugle corps, glee club, and camp orchestra, which delivered performances once a month. MP-1 also offered different school programs, including life saving, company clerks, and first aid attendants. In April 1934, a camp newspaper titled The Renaissance News began publication as an education opportunity for enrollees who could contribute articles of interest.[25] Due to its high degree of efficiency and excellent morale, Company 385-C was given the honor of being the best camp in the sub-district in May 1935.

News that a second CCC camp would be established at Gettysburg appeared in local newspapers in September 1933. Superintendent McConaghie was able to justify the need for more labor and his request for another company was accepted. MP-2 was placed in McMillan’s Woods, also on Seminary Ridge, and operated until March 1942.[26] MP-2 was occupied by Company 238-C, Captain James M. MacDonnell commanding, on October 18, but their time in Gettysburg was relatively short. Local newspapers reported in early May 1934 that Company 238-C would be sent to Yaphank, New York on May 9, leaving an open camp for a new company of enrollees.[27]

Company 1355-C was then assigned to MP-2. Organized at Fort George G. Meade, Company 1355-C arrived at Gettysburg on May 26, 1934 with three white officers and 190 African American enrollees.[28] Though it was organizationally similar to Company 385-C when it was created, Company 1355-C would stand out as one of the most unique companies in the CCC program.

Enrollees at work cleaning the High Water Mark Monument on Cemetery Ridge, 1937.

In August 1936, Captain Oscar H. Coble, the commanding officer at MP-2, learned that he and every white officer were to be transferred out. On August 10, Captain Frederick L. Slade, 1st Lieutenant George W. Webb, and 2nd Lieutenant Samuel W. Tucker, all African Americans, took command of the camp. This change in command came as a surprise to the white officers, and when the Gettysburg Times failed to ascertain the reasons behind the abrupt changes, the paper reported it was “believed to be an experiment of colored supervision of colored enrollees in the CCC camps.”[29] Slade became the first black officer to command a black CCC camp in the country, and by 1939 MP-2 was led by an all-black staff and served as “a ‘model’ camp of negroes.”[30] This “experiment” was, not surprisingly, successful.

There was plenty of work on the battlefield for the enrollees of Company 1355-C to perform. Work assignments mirrored those of Company 385-C. They included road installation, planting and pruning trees, clearing brush, cutting and hauling timber, building stone and rail fences, cleaning monuments, and other projects outlined by the National Park Service.[31] One of the more delicate jobs enrollees performed was that of resetting the grave markers of the Union dead in the National Cemetery. The sacredness of the job was not lost on the men. One enrollee, Frank Deering, was so inspired by the cemetery and his time working in it that he wrote a poem he titled “Remembering.” It read:

In this graveyard one can see,

The graves of the boys of sixty-three.

Only a few remember the day,

When these brave heroes were laid away.The soldiers fought to set us free,

And we, the boys of the C.C.C.,

Pay our respect to the boys in blue,

Who nobly fell for a cause so true.We care for the plot where their bodies rest,

And with reverent hearts we do our best.

To keep their final resting place,

A thing of beauty and of grace.[32]

Enrollees at MP-2 had numerous opportunities to discover and learn new interests. MP-2 hosted sports activities similar to those at MP-1, but with the addition of touch football and pool. Some of the enrollees showed considerable talent in their activities, as some of the men received commendations for boxing and swimming. Enrollees took advantage of the various educational opportunities at their disposal. Upon the expiration of their service, some enrollees planned to complete or further their educations by returning to high school or going on to college or vocational programs. The company started a camp newspaper as well, first with the M. P. Mirror and then The Battlefield Echo.[33] For its excellence in camp and enrollee health, religious morale and welfare activities, and the company’s administration, Company 1355-C in May 1941 was named a superior camp within its district of ten camps and was awarded the district honor flag. Company commander 1st Lieutenant George W. Webb rewarded his men with a special dance that was open to the community.[34]

CCC camps across the nation attempted to establish a level of transparency with the communities around them and highlight the program’s success. MP-1 and MP-2 were no exception. On March 30, 1938 MP-2 announced its schedule of events and special speakers for a weeklong commemoration. Activities ranged from camp tours led by “specially selected guides,” to a film of the projects carried out by the enrollees, to musical performances by the company glee club, to an address titled “The Significance of the C.C.C. at Gettysburg” delivered by National Park Service historian Dr. Louis E. King. The weeklong observance culminated on April 5, the birthday of the CCC, with an address delivered by Dr. Dwight O. W. Holmes, president of Morgan College in Baltimore, Maryland.[35]

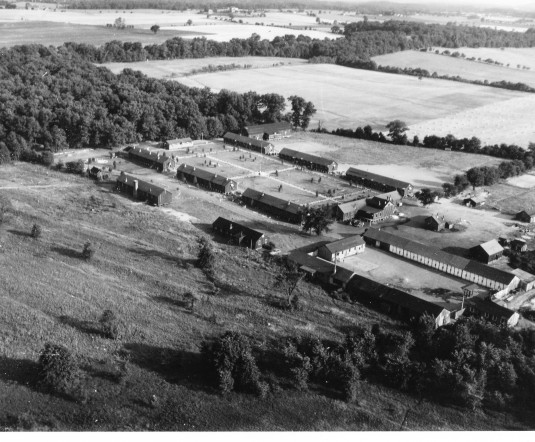

CCC Camp MP-2, aerial view of McMillan Woods, West Confederate Ave., October, 1941 (from northwest).

1938 was a special year for the surviving veterans of the Civil War, the citizens of Gettysburg, the National Park Service, and most of all, the nation. 1938 marked the seventy-fifth anniversary of the battle, and would witness the final reunion for the aging Union and Confederate veterans. Company 1355-C played a role in getting the event up and running. Enrollees assisted in constructing the Eternal Light Peace Memorial and setting the gas line to fuel the monument’s flame. They also worked with Army personnel to construct various structures for the ceremonies and a camp for over 1,800 veterans who attended. Army officers and enlisted men began to arrive to the town in June and were quartered at the abandoned MP-1. Those soldiers occupied MP-1 until at least August in order to dismantle the veterans’ camp and perform additional clean-up work.[36]

The culmination of the 1938 commemorative event was an address delivered by President Roosevelt on July 3 at the Eternal Light Piece Memorial on Oak Hill. A central theme of Roosevelt’s speech was unity. “On behalf of the people of the United States,” Roosevelt began, “I accept this monument in the spirit of brotherhood and peace.”[37] Then, before an audience of some 250,000 spectators, possibly more, Roosevelt said of the veterans, “They are brought here by the memories of old divided loyalties, but they meet here in united loyalty to a united cause which the unfolding years have made it easier to see.”[38] Roosevelt’s emphasis of unity between former enemies underscored the necessity of a nation uniting to create a better world for the present as well as future generations. While Roosevelt spoke specifically to the slowly disappearing animosity between the blue and gray, he overlooked the growing hostility between white and black, but perhaps Americans of every race, ethnicity, and religion could use those aging men as an example to establish a new “brotherhood and peace.”

The memory of the CCC at Gettysburg continues to live on through their work that still stands on the battlefield – though many of their contributions go unnoticed to visitors today. The enrollees installed or improved park roads such as Jones’ Battalion Avenue, Sykes Avenue, and Wheatfield Road. They installed or improved trails on Little Round Top, Big Round Top, and at Devil’s Den. They landscaped around the West and South End Guide Stations, at Little Round Top, and around the Alabama Monument. They cleaned various monuments such as the High Water Mark Memorial, the Vermont State Monument, and the monument to the 155th Pennsylvania Volunteers. They widened the gateway to the National Cemetery from Baltimore Pike and reset the gravestones inside the National Cemetery. They removed, installed, or relocated stone walls and various types of fences, such as the stone wall along Granite School House Lane, the stone wall facing the parking lot on Little Round Top, and the iron picket fence separating the National Cemetery and Evergreen Cemetery. They constructed the parking lots on Culp’s Hill, Devils Den, and Steven’s Knoll. The Gettysburg battlefield that so many Americans know and cherish was shaped by the black enrollees of companies 385-C and 1355-C.

Enrollees constructing a sidewalk on Little Round Top, ca. 1936.

The work performed by the black enrollees on the battlefield can be easily measured. By June 1935, two years into the program, MP-1 and MP-2 had removed fire hazards from over 800 acres and performed general cleanup to 1,163 acres of battlefield land. MP-1 had repaired 19 wells and water holes, performed 11,154 square yards worth of fine grading, and installed 700 linear feet of pipe lines and conduits. MP-2 installed 6,023 cubic yards of guard rails and stone walls, performed 32,848 square yards worth of fine grading, and reset 786 gravestones in the National Cemetery.[39] This was just the beginning for a program that would exist for seven more years at Gettysburg. What cannot be easily measured, however, is the impact the CCC had on the individual enrollees of companies 385-C and 1355-C, or even the influence of Gettysburg’s national significance on those young men.

The presence of the CCC program and African American enrollees at Gettysburg left an indelible legacy on the community and the battlefield. The work performed by companies 385-C and 1355-C serve as a living testimony to their contributions to their own and future generations of Americans. Through their energies on the Gettysburg battlefield, and the prejudice they faced, the black enrollees dedicated themselves to the “unfinished work” that was “so nobly advanced” on the nation’s Civil War battlefields. The service by the enrollees to themselves and their nation contributed in an immeasurable way to fulfilling President Abraham Lincoln’s hope for a “new birth of freedom.”

Casimer Rosiecki, Park Ranger

I would like to extend my gratitude to the following individuals and organizations for their assistance with helping me research the CCC at Gettysburg: The Adams County Historical Society in Gettysburg, PA; John C. Frye, Western Maryland Room Curator, and Elizabeth Howe, Associate Librarian, Washington County Free Library in Hagerstown, MD; Paul T. Fagley, Cultural Educator at Greenwood Furnace State Park Complex, Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources; John Eastlake, who has done much work on the CCC in Pennsylvania; Joan Sharpe, President, CCC Legacy; and Andrew Newman, Museum Technician, Gettysburg National Military Park.

[1] Franklin D. Roosevelt, “Inaugural Address. March 4, 1933,” in The Public Papers and Addresses of Franklin D. Roosevelt with a Special Introduction and Explanatory Notes by President Roosevelt, vol. 2, (New York: Random House, Inc., 1938), 13. Hereafter cited as “Roosevelt”.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] “The New Deal Years: 1933-1941,” in America’s National Park System: The Critical Documents, ed. Lary M. Dilsaver (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 1994), accessed February 28, 2015, http://www.cr.nps.gov/history/online_books/anps/anps_3a.htm.

[6] Roosevelt, 107-110.

[7] Ibid., 109-110.

[8] Joseph M. Speakman, At Work in Penn’s Woods: The Civilian Conservation Corps in Pennsylvania (University Park, PA: The Pennsylvania University Press, 2006), 131. Hereafter cited as “Speakman”.

[9] Olen Cole, Jr., The African-American Experience in the Civilian Conservation Corps (Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida, 1999), 13-14.

[10] Ibid., 11.

[11] Speakman, 142-143.

[12] C.C.C. Annual 1936: District No. 1, Third Corps Area (Baton Rouge, LA: Direct Advertising Company, 1936), 199. Hereafter cited as “CCC Annual 1936”.

[13] Ibid.

[14] “206 RECRUITS ARRIVE HERE THIS MORNING,” Gettysburg Times (Gettysburg, PA), June 10, 1933.

[15] “206 RECRUITS ARRIVE HERE THIS MORNING,” Gettysburg Times (Gettysburg, PA), June 10, 1933.

[16] Speakman, 135.

[17] “SEEK TO KEEP CCC CAMP HERE,” Gettysburg Times (Gettysburg, PA), March 14, 1936.

[18] CCC Annual 1936, 199.

[19] “Twister Causes Much Damage as It Sweeps Through Here Sunday,” Gettysburg Times (Gettysburg, PA), July 3, 1933.

[20] “Captain Moran Rejects “Gift” of Two “Bombs” From Innocent Recruits,” Gettysburg Compiler (Gettysburg, PA), March 1, 1934.

[21] CCC Annual 1936, 199.

[22] “CCC MEN FIGHT MOUNTAIN FIRE,” Gettysburg Times (Gettysburg, PA), May 4, 1936.

[23] Roosevelt, 81.

[24] Ibid.

[25] CCC Annual 1936, 199.

[26] “CCC CAMP HERE WILL BE CLOSED ABOUT MARCH 15,” Gettysburg Times (Gettysburg PA), March 6, 1942.

[27] “COMPANY 238 MOVES MAY 9,” Gettysburg Times (Gettysburg, PA), May 3, 1934.

[28] CCC Annual 1936, 211.

[29] “NEGRO OFFICERS TAKE CHARGE OF CCC CAMP HERE,” Gettysburg Times (Gettysburg, PA), August 8, 1936.

[30] “Battlefield C.C.C. Camp To Be First One in U.S. Under All-Colored Staff,” Gettysburg Times (Gettysburg, PA), November 4, 1939.

[31] CCC Annual 1936, 211.

[32] “Writes Poem On National Cemetery,” Gettysburg Times (Gettysburg, PA), December 30, 1935.

[33] Ibid.

[34] “BATTLEFIELD CCC CAMP IS BEST IN AREA,” Gettysburg Times (Gettysburg, PA), May 29, 1941.

[35] “C.C.C. Camp Here Arranges 5th Anniversary Program,” Gettysburg Times (Gettysburg, PA), March 30, 1938.

[36] “90 Soldiers Stationed At Former C.C.C. Camp,” Gettysburg Compiler (Gettysburg, PA), July 30, 1938.

[37] Franklin D. Roosevelt, “‘Avoiding War, We Seek Our Ends Through the Peaceful Process of Popular Government Under the Constitution.’ Address at the Dedication of the Memorial on the Gettysburg Battlefield, Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, July 3, 1938,” in The Public Papers and Addresses of Franklin D. Roosevelt with a Special Introduction and Explanatory Notes by President Roosevelt, 1938 Vol., (New York: Random House, Inc., 1941), 419, accessed February 28, 2015, https://archive.org/details/4926315.1938.001.umich.edu.

[38] Ibid., 420.

[39] “$72,896 Is Spent For CCC Labor on Battlefield Here,” Gettysburg Compiler (Gettysburg, PA) June 29, 1935.

This is a most read for anyone interested in the history of the GNMP.

On 3/26/15, The Blog of Gettysburg National Military Park

Such a brave people to support the military movement for everyone’s future leading to peace. Honoring them with respect and gratitude.