The Great Reunion of 1913, marking the 50th Anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg, is often seen as a time of reconciliation. The nation had engaged in the Spanish-American War (1898) that saw the two sections coming together to confront a common enemy and which saw many ex-Confederates donning blue army uniforms. But the veterans had come together 25 years earlier in 1888 to pledge loyalty to one country, one constitution, and one flag.

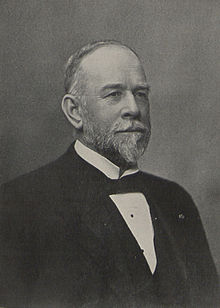

Daniel E. Sickles (Image courtesy of the Library of Congress)

At the reunion of the Society of the Army of the Potomac held in 1887, Major General Daniel E. Sickles, who had commanded the Third Corps of the Army of the Potomac at the battle of Gettysburg, introduced some resolutions for the next reunion. The resolutions provided for a 25th reunion of the survivors of the Army of the Potomac to meet on the Gettysburg Battlefield on July 1, 2, and 3, 1888. The resolutions also stipulated that the survivors of the Army of Northern Virginia be invited. The intention was that the survivors of these once opposing armies “might on that occasion record in friendship and fraternity the sentiments of good-will, loyalty, and patriotism which now unite all in sincere devotion to the country.”

The veterans, averaging in their fifties, began arriving in Gettysburg in the last week of June 1888. Over the next several days, thousands of Union veterans once again descended upon the town, but just a little more than three hundred Confederates were able to attend. For most Confederate veterans, the journey was either too far, too expensive, or the invitations had arrived too late for some to make plans to attend. One newspaper estimated that there were up to 30,000 veterans, soldiers and civilians, on the battlefield. It was noted that no gathering since the battle “has equaled that of the twenty-fifth anniversary of the great event.”

One magazine noted that the “unique and striking feature of the Gettysburg reunion was the fraternal assemblage of men who had, on the same field, fought each other to the death for principles incapable of reconciliation.”

Joshua Chamberlain, Daniel Butterfield, James Longstreet, and Daniel E. Sickles on the Gettysburg battlefield, 1888. (GNMP)

Among the most prominent Union officers to attend were Major Generals Daniel E. Sickles, aged 69, and Henry W. Slocum, aged 61, who had commanded the Union Twelfth Corps. Lieutenant General James Longstreet, aged 67, who had commanded the First Corps of Lee’s army, and Major General John B. Gordon, aged 56, who had commanded a brigade at Gettysburg and was now the governor of Georgia, were the ranking officers representing the South.

One thousand tents had been erected on East Cemetery Hill for the Pennsylvania Grand Army of the Republic (GAR) encampment. Tents were also erected in the Wheatfield for the New Jersey National Guard. Contingents from the U. S. Army were encamped at Reynolds’ Grove and the Springs Hotel. The Springs Hotel, which was located about one mile from town on the west side of Willoughby Run, near the current site of the Gettysburg Swim and Tennis, was the scene of the encampment on the 9th New York State Militia. This unit had served in the battle as the 83rd New York Volunteers. All the hotels in town were booked for the occasion. Confederate General James Longstreet was also staying at the Springs Hotel. Shortly after his arrival at the hotel on June 30, Longstreet was at the center of a group consisting of former Union generals Lucius Fairchild and John C. Robinson and Governor James A. Beaver of Pennsylvania.

It was reported that “hundreds” had started from town to see Longstreet when word was received that he had checked into the hotel. But just before the crowd “hove in sight the dashing ex-Confederate was whisked off to Reynolds’ Grove to participate in the dedication of the monuments to commemorate the deeds and the dead of Wisconsin’s ‘Iron Brigade.’”

On July 1 the First Corps from the Army of the Potomac held their exercises at Reynolds’ Woods (now Herbst’s Woods). One special guest was former Confederate Lieutenant General James Longstreet. Longstreet was approached by a one-legged veteran who hobbled up on his crutches to the General “and, grasping his hand, said: ‘General, I fought against you at Round Top. I lost a wing there, but I am proud to meet you here’ Gen. Longstreet’s face beamed with satisfaction as he grasped the extended hand, and said: ‘Yes, those were hot times then; but I’m all right now.” It was reported that three cheers were proposed for Gen. Longstreet “which were given with a will by some 10,000 veterans who had fought against this General from Georgia.”

On the morning of July 2, Longstreet was the guest of Major General Henry W. Slocum of New York at the dedication of several New York monuments on Culp’s Hill. Before the ceremonies began, Longstreet “was decorated with a red rose and a miniature American flag by Miss Sadie Cressey.”

The Grand Reunion was scheduled for the afternoon of July 2, 1888, at the rostrum in the Gettysburg National Cemetery. The New York Times reported that this reunion was “the most dignified and inspiring of any of the meetings of survivors of the war that have occurred since Appomattox.” The New York Times also noted that the “actors were the very men who defended this ridge on whose slope the cemetery lies against the repeated and desperate assaults led by the very men 25 years ago this very day who joined them here now in pledges of friendship, loyalty to a common flag, and unity of devotion to a common country. All – place, scene, and the living figures of the men themselves – was inspiring.”

Gettysburg National Cemetery. The New York Times reported that this reunion was “the most dignified and inspiring of any of the meetings of survivors of the war that have occurred since Appomattox.” The New York Times also noted that the “actors were the very men who defended this ridge on whose slope the cemetery lies against the repeated and desperate assaults led by the very men 25 years ago this very day who joined them here now in pledges of friendship, loyalty to a common flag, and unity of devotion to a common country. All – place, scene, and the living figures of the men themselves – was inspiring.”

The grand procession began moving down Baltimore Street at 4:30 p.m. Colonel Horatio Gates Gibson, 3rd US Artillery, with two aides led the procession. He was followed by the Artillery Band and a contingent of U. S. Army Regular troops. A local paper wrote that “Uncle Sam’s men never looked better nor marched better, and, of course, they inspired admiration along the whole route.” Luciano Conterno’s 60-piece band led the 9th New York State Militia which was followed by more cavalry. Following the military contingents came state and other military officials and the veteran organizations. The Grand Army of the Republic posts that were present followed. Most of the G.A.R. posts had their own drum corps. The noise “was perhaps only excelled by the din which 25 years ago was made by the artillery of both armies.” It was reported that a squad of about 30 of Pickett’s men “attracted much attention, but all of a pleasant nature.”

While none of the marching troops were allowed inside the Gettysburg National Cemetery grounds, “the veterans and the throng of people poured through and gathered about the arbor at the western end of the great inclosure….there must have been 5,000 of them.” The ceremonies took place at the brick rostrum, which had been erected in 1878, and is at the Taneytown Road entrance to the cemetery.

Sitting on the rostrum “could be seen Gens. Sickles, Longstreet, Slocum and Gordon, who [once] were fighting and trying with all their powers to kill each other at the time of the great action; but now they sat there with the best of feelings toward each other. It was a queer sight to thus see these leaders on opposite sides engaged in friendly intercourse before the vast assemblage which had gathered in the cemetery, the like of which will, perhaps, never be looked upon again.”

Among the other Gettysburg veterans on the rostrum were generals Francis C. Barlow, James C. Robinson, and Samuel W. Crawford, all Union division commanders. Also present were Union brigadier generals Joseph B. Carr, Charles K. Graham, Hiram Berdan, and J. H. Hobart Ward, and Major General Daniel Butterfield, Gen. Meade’s chief of staff during the battle. Brevet Brigadier General James C. Lynch, former captain of the 106th Pennsylvania, who later served as colonel of the 183rd Pennsylvania, was also present.

Joseph Hopkins Twichell

At about 5:00 p.m., the Rev. Joseph Hopkins Twichell (1838 – 1918), the former chaplain of the 71st New York Infantry and a Gettysburg veteran, gave the invocation. Twichell was

the pastor of the Asylum Hill Congregational Church in Hartford, Connecticut, and had been a close friend of Mark Twain since their first meeting in 1868.

Brigadier General John C. Robinson (1817 – 1897), the master of ceremonies, had been commissioned directly into the U. S. Army in 1839 from New York. He served as colonel of the 1st Michigan Infantry and was promoted to brigadier general on April 28, 1862. He lost a leg at Spotsylvania in 1864 and had commanded the Second Division of the First Corps at Gettysburg. He had served as lieutenant governor of New York (1872 – 1874) and was now serving as commander-in-chief of the Grand Army of the Republic and as president of the Society of the Army of the Potomac.

General Robinson introduced Major General Daniel E. Sickles (1819 – 1914), “leonine and impressive as he ever is,” as the presiding officer of the reunion. Sickles had served as a U. S. Congressman (1857 – 1861) and organized the Excelsior Brigade at the beginning of the Civil War. He was made a brigadier general on September 3, 1861, and a major general on November 29, 1862. He lost his leg during the fighting at Gettysburg. He later served as minister to Spain (1869 – 1874), chairman of the New York State Monument Commission, and chairman of the New York Board of Civil Service Commissioners (1888 – 1889). A local paper wrote that Sickles’ speech sounded “the key note for the pleasing interchange of fraternal greetings on the part of men prominent on either side. At the end of his comments, Gen. Sickles stated:

Twenty-five years have passed, and now the combatants of ’63 come together again on your old field of battle to unite in pledges of love and devotion to one constitution, one Union and one flag. To-day there are no victors, no vanquished. As Americans we may all claim a common share in the glories of this battlefield, memorable for so many brilliant feats of arms. No stain rests on the colors of any battalion, battery or troop that contended here for victory. Gallant Buford, who began the battle, and brave Pickett, who closed the struggle, fitly represent the intrepid hosts that for three days rivaled each other in titles of martial renown.

Sickles then introduced Major General John B. Gordon (1832 – 1904), a brigade commander in the Army of Northern Virginia at Gettysburg and now governor of Georgia. Gordon was described as “tall, slender, with long black hair, cured under at the ends in the old Southern style, and with a hard, cruel, gambler-like face, disfigured by a deep scar made by a Yankee bullet.” There was frequent applause as Gordon’s “swinging sentences, eloquent and ringing, were uttered.” General Gordon greeted the assembled old soldiers with less trepidation than in 1863. He noted that they were meeting today as citizens of a common country with no break in the line from Maine to Florida. There was one suggestion that dominated his thoughts and he asked for a brief indulgence:

My fellow countrymen of the North, if I may be permitted to speak for those whom I represent, let me assure you that in the profoundest depths of their nature they reciprocate that generosity with all the manliness and sincerity of which brave men are capable. In token of that sincerity they join in consecrating for annual patriotic pilgrimage these historic heights, which drained such copious drafts of American blood poured so freely in discharge of duty, as each conceived it, a Mecca for the North, which so grandly defended it; a Mecca for the South, which so bravely and persistently stormed it; we join you in setting apart this land as an enduring monument of peace, brotherhood, and perpetual union.

Gordon repeated his thought “with additional emphasis, with singleness of heart and of purpose, in the name of a common country, and of universal human liberty, and by the blood of our fallen brothers, we unite in the solemn consecration of these battle-hallowed hills as a holy eternal pledge of fidelity to the life, freedom and unity of this cherished republic.”

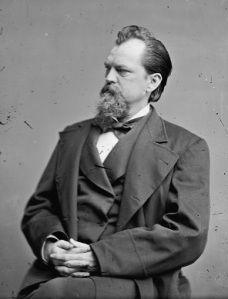

James A. Beaver

General Robinson next introduced James A. Beaver, Governor of Pennsylvania and a trustee of the Pennsylvania State University. “The glowing tribute,” given by General Robinson, “that was paid him (Beaver) as soldier, statesman, and patriot was the signal for another outburst of applause and three hearty cheers.” James A. Beaver (1837 – 1914) had served as lieutenant colonel of the 45th Pennsylvania Infantry and later recruited and served as colonel of the 148th Pennsylvania Infantry. The regiment saw action at Gettysburg, but Colonel Beaver, not being fully recovered from a wound received at Chancellorsville, was not allowed to assume command. He later lost his leg at the battle of Ream’s Station in June 1864. He refused higher commands because he did not feel it right to leave the men he had recruited for the 148th. He served on the board of trustees for the Pennsylvania State University (1873 – 1882) and was in his second year as governor of Pennsylvania (1887 – 1891). Beaver Stadium at Penn State’s main campus is named in his honor.

Governor Beaver had been appointed by his comrades in the Army of the Potomac to give “a simple but sincere welcome” to the Confederate veterans. He pointed to the fact that at one time the whole people lived under a compact called the Constitution. This compact was subject to “divers and diverse interpretations.” Since the ordinary forms of government could not decide the issues it had to be left to the dread arbitration of war. “But,” the governor stated, “we are now citizens of a common country; claiming no superiority, admitting no inferiority, each claiming to be American citizens in all the attributes of the glorious name.” Governor Beaver concluded by saying:

You and I have something to do with the future. Our faces are to be resolutely turned to the front. The hand which beckons us points forward, not backward, and it is in recognition of this fact and because that we, as wearers of the gray and blue can exert and should exert a great influence in shaping the destiny of this country, that my comrades of the Army of the Potomac have invited you here that we may look each other in the face, may assure you of our desire to accord to you your full share in the work which is before us, of our sympathy in the heroic effort which you have made and are still making in building up a new South, and of our admiration for the courage and fortitude, and the endurance with which you sustained your side of the contest to which I have alluded – whose decision is beyond recall….We welcome you because we need you; we welcome you because you need us; we welcome you because we together must enter into and possess this future, and transmit this heritage to the oncoming generations. If so, let the dead past bury its dead.

Charles E. Hooker

Rev. J. C. McCabe of Virginia, a former chaplain in the Confederate Provisional Army, was to have given a response to Governor Beaver, but he was unable to be present due to a railroad delay. Instead, General Charles Edward Hooker of Mississippi (1825 – 1914) responded to the address of Governor Beaver. General Hooker, a graduate of Harvard Law School, had entered the Confederate army as a private but soon became a lieutenant and a captain of the First Regiment of Mississippi Light Artillery. He was promoted to the rank of colonel of cavalry. He served in the U. S. Congress from 1875 – 1883 and was elected to serve in the Fiftieth Congress starting on March 4, 1887.

It was reported that even though Hooker’s “effort was extemporaneous; it was a splendid one, which evoked great applause.” General Hooker stated that he had not intended to come here and say anything. He had been moved by the generous spirit that extended the invitation to the soldiers of the gray to meet the soldiers of the blue in Gettysburg. Among his remarks General Hooker stated that: “Shall we of the Confederacy, who delight to recall the brilliant and dashing charge of Pickett, the less admire the stubborn and successful resistance of the ‘Iron Brigade?’ They were all Americans, and the American heart is large enough, and American history true enough, to record the valor of all, and claim it as a common heritage.”

General Hooker concluded by saying:

We should be something more or less than men and women could we forget the perils encountered, the hardships endured, and the blood shed for us by the boys who wore the blue and the boys who wore the gray. Their last syllabled utterances as they fell on this and many another distant battle-field as their pale lips froze in death perchance murmured our names. No! their memories must be ever cherished, not in hate, but in love; and as we go from this field let us feel nerved anew for the struggle of life and the development of our glorious county.

While the applause was still going on for General Hooker, General James Longstreet (1821 – 1904) “came quietly on the stand, and after shaking hands with Gens. Sickles and Gordon took a seat near the later.” Longstreet was described as “tall, large-framed, and wearing luxuriant white whiskers.”

General Sickles introduced the venerable war governor of Pennsylvania, Andrew G. Curtin (1817 – 1894), with a few fitting remarks. Curtin had served as governor (1861 – 1867), minister to Russia (1869 – 1872), and a U. S. congressman (1881 – 1887). Governor Curtin “walked feebly to the rail which runs along the edge of the rostrum. His short talk convulsed the crowd with laughter.” However, no one reported the exact words of Governor Curtin or of the speakers who followed him.

General Longstreet then spoke a few short sentences. He was followed by Major General Henry Slocum (1827 – 1894), commander of the Union Twelfth Corps on Culp’s Hill, who addressed the audience for a short time.

The final speaker was General Martin Newton Curtis (1835 – 1910), the former commander of the 142nd New York and who was promoted to brigadier general on January 15, 1865. In 1891, he would be awarded the Medal of Honor for action at Fort Fisher, North Carolina, in January 1865. He was a member of the New York State Assembly (1884 – 1890) and was currently the commander of the New York chapter of the Grand Army of the Republic.

At one point in the proceedings, General Sickles read a telegram from Mrs. George E. Pickett:

When I accepted the suggestions of kind friends that my presence would serve as a link in the chain of unity between the sections broken by civil war I was ready and most willing to make any sacrifice to contribute to perfect union of the survivors of blue and gray upon the field consecrated by the bleeding of the blood of the bravest men ever upon God’s footstool. But knowing that the wings of sweet peace are in unity blended so that no single person can bind them more closely, and the condition of my health admonishing quiet, I tender thanks and God’s blessing instead of my presence.

President Grover Cleveland had also been invited to attend the Grand Reunion, but he concluded that because “of my confining duties here [Washington] and all the circumstances surrounding the subject, I have arrived at the conclusion that I ought not to leave here at the time designated.” The President did feel that the “meeting of the survivors of Gettysburg upon the field where they fought twenty-five years ago cannot fail to teach an impressive lesson and convince all our people that bravery is akin to magnanimity, while it reminds them that the object of war is the attainment of peace.”

The Rev. Dr. Milton Valentine (1825 – 1906), 3rd President of Gettysburg College and currently the chairman of the faculty at the Lutheran Theological Seminary in Gettysburg, closed the exercises with a benediction. The “immense crowd broke up and amused itself in strolling over the graves, reading the headstones, and gazing upon the beautiful monuments.” The half circle of graves radiating out from the Soldiers’ National Monument contained the remains of 3,500 Union dead from the battle of Gettysburg. The stones marking the graves had been installed in the summer of 1865. The Minnesota Urn, the oldest monument on the battlefield, had been erected in 1867. The Soldiers’ National Monument had been dedicated in 1869.

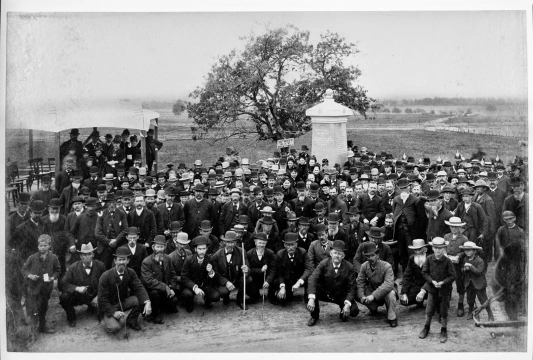

Veterans of the 12th New Jersey dedicate their monument, June 30, 1888.

While July 2 was the official day of reunion, good feelings prevailed over the entire time of the anniversary of the battle. General Longstreet, for example, was conspicuously present at several events. On July 1, he was present at the reunion of the Union Army First Corps at Reynolds’ Woods. So many of the Union veterans wanted to shake Longstreet’s hand that the platform on which they were standing collapsed. Fortunately, no one was hurt. No hard feelings were expressed in any of the official or unofficial remarks. If any hard feelings remained no one mentioned them. This was a time to celebrate the sacrifices made on the field by the soldiers of both sides and to celebrate the fact that the veterans again lived in a united country under one flag and under one constitution.

Karlton Smith, Park Ranger

Gettysburg National Military Park

Great article, so many great pictures. Thanks!

Great research. Nicely done, Karlton!

Interesting article. I’m curious who had the means to attend but chose not to, and why.

I see no mention of freed slaves or black veterans in attendance….the unity and brotherhood here was for white men only, it seems.

The reunion at Gettysburg in 1888 was primarily for Union veterans of the “Army of the Potomac”, which was indeed composed of white soldiers. African American Union veterans primarily served in the Army of the James, the Ninth Corps, and Department of the Carolinas, so were not veterans of the battle. There is no evidence that black veterans were intentionally excluded from the official invitation to attend.

Pingback: Sunday Talk Shows | Dixie Gone With The Wind