One of most harrowing stories of the battle of Gettysburg is the experience of the 9th Massachusetts Battery. Told again and again through publications and by the monuments that mark the battery’s position at the park, it’s near destruction adjacent to the Abraham Trostle farm buildings on July 2, 1863, was documented not only in reports by the survivors but also by Alexander Gardner’s camera- the disturbing photograph of bloated carcasses of artillery horses splayed over the site of the battery’s last stand that horrid afternoon.

The Abraham Trostle Farm house photographed by Alexander Gardner soon after the battle, the scene where the 9th Massachusetts Battery made its final stand on July 2, 1863. (LOC)

After retiring by prolong from their first position on the Wheatfield Road, the battery halted to limber their guns in the small orchard south of the Trostle farm buildings. But in the mad dash through the gate in the stone wall near the house, the first gun overturned, completely blocking the only way out. Though an additional piece was able to drive over the wall itself to escape, the remaining four were trapped. Immediately the gunners unlimbered “into battery” and the fight for their very lives began as the 21st Mississippi Infantry swept upon them like a lightning bolt.

It was unrestrained violence. Blasts of canister from the guns were answered by a storm of rifle fire that laced man and animal alike. Harnessed to their limbers, the horses fell in heaps, their groans of alarm mixed with the hellish roar of guns and small arms, shouting gunners and drivers, and the high pitched rebel yell. Captain John Bigelow, commanding the doomed battery, was shot from his horse and looked up to see gray-clad Mississippians standing on the limbers, shooting point blank into his trapped gunners and drivers, all scrambling to escape the trap in this bloody corner of Trostle’s orchard.

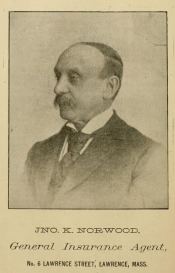

In the tumult of battle, Private John K. Norwood was serving his piece, the Number 5 gun, when every member of his crew was shot down. Born in Maine, the twenty four year-old Norwood had moved to Lawrence, Massachusetts to start a new life and was a clerk in a dry goods business when he volunteered for service in 1862. He and several others from Lawrence were assigned to the 9th Battery, in which he proved efficient enough to serve on a gun crew. The somewhat harsh and difficult training he and his mates had received under Captain John Bigelow the previous winter had served him well in his first major battle but nothing could have prepared him for this- a tide of howling Confederates bent on destroying him and those who stood by the guns and limbers.

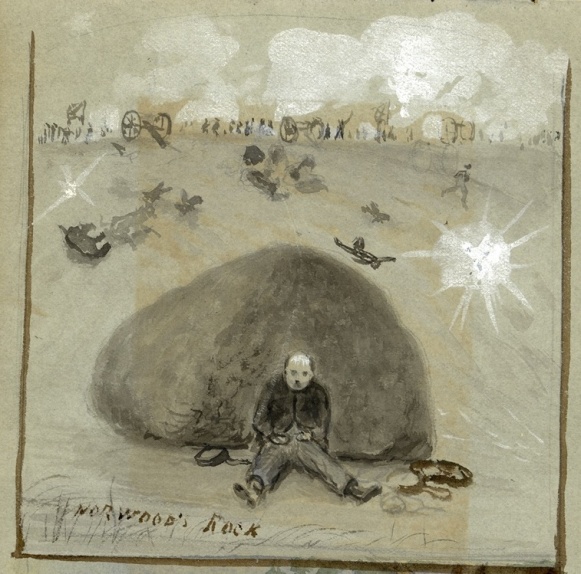

Orders were shouted to get out as quickly as possible and as he and a driver were desperately trying to limber the number five gun, Norwood, “was shot through the lungs,” the bullet crashing through his chest and lodging near his spine. “No one else there and the remaining horses shot(,) the enemy were on the gun and limber, and a color bearer mounted the limber and waved his flag.” Norwood collapsed by the trail of gun, the melee continuing around him as he crawled under the piece to take advantage of what little shelter it offered. Fortunately, Private Ralph Blaidsell, unharmed at the moment, saw his comrade fall and crawled to Norwood as the Confederates passed through the wreckage in pursuit of retreating Federals. Blaidsell instructed Norwood to lay still, he would follow the Confederate line to fetch water for his wounded comrade. The handful of Confederates milling about let Blaidsell pass to bring water back to Norwood and during a brief lull in the fighting, assisted the wounded soldier, “fifty yards to the shelter of a large tree and bowlder(sic) under it.” In the final minutes of the fighting at dusk, retreating Confederates took shelter on the other side of the boulder and fired over it at pursuing Federal troops who recaptured the battery’s abandoned guns. [i]

Holland’s sketch of the severely wounded Pvt. Norwood behind the boulder in Trostle’s field. (S. McClintock Collection)

Unable to be taken off the field that night, the weak and exhausted Norwood stayed behind the shelter of the boulder “where he lay and kept the wound wet all night” with the precious water Blaidsell had brought him. Early the next morning and with the assistance of a Confederate skirmisher, Norwood stumbled into the Trostle house to take shelter along with a handful of other wounded men. It was not until that evening could the severely injured soldiers be reached and taken to a farm on the Baltimore Pike.[i]

Norwood survived his terrible wound but never returned to the battery or the army. Discharged for disability on February 1, 1864, he went home to Lawrence with the Confederate bullet that Union surgeons could not extract without killing him still lodged in his chest. It would be another three years before he was strong enough to try his hand at business again. In 1867, Mr. Norwood opened an insurance company in Lawrence, the same year his son Kendall was born followed by a daughter ten years later. The prosperous businessman was elected president of civic organizations, active in the Grand Army of the Republic as a member in good standing of GAR Post 39 in Lawrence, and soon after elected president of the 9th Massachusetts Battery Association.

In the spring of 1883, for the first time since the battle, John Norwood stood again on the spot where his battery met their bloody test and where he barely survived the gunshot wound through his lungs. As part of an excursion to mark the locations for Massachusetts monuments at Gettysburg, it was his responsibility to agree on the site where the battery’s monument should stand. His visit had to be somewhat of a shock for the battlefield had changed over time and a disagreement ensued with John Bachelder, the Gettysburg Battlefield Memorial Association’s historian, on where the monument should go. Not satisfied with Colonel Bachelder’s choice, he returned the following year with a committee composed of former members of the battery. Among them was veteran Richard Holland of North Bridgewater (Brockton, MA), an Irish-born immigrant who had settled in Massachusetts and answered the same call for volunteers in 1862 as did Norwood. It was a congenial relationship that began during their first weeks in service with the 9th Massachusetts Battery.

Holland was one three artists who served with the battery; Charles Reed and Isaac Eaton being the other two, both recognized in the post war period for their soldier art while Holland enjoyed drawing and painting landscapes. As the men walked the field where their old battery had fought, the stories of each man’s experiences were passed and as they stood near the corner of the fateful field near Trostle’s house, Norwood related his experience in taking shelter behind the large boulder under the tree and how he survived the night, finishing his description of the farm on the Baltimore Pike where he was taken to for medical care.

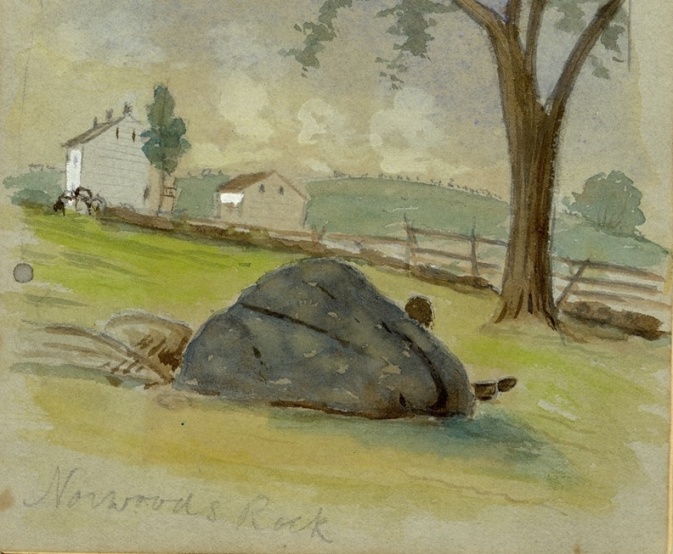

Holland’s second sketch of Norwood behind his boulder near the Trostle House. (S. McClintock Collection)

Returning to Massachusetts, the committee proposed not just one monument but three to mark where the battery had so valiantly served on July 2 and 3 on the Gettysburg battlefield. The additions were reviewed and approved by the state committee. Dedicated on October 19, 1885, the monument to the 9th Massachusetts Battery stands on the Wheatfield Road with second position markers in Ziegler’s Grove and at the Trostle Farm next to the site of the gateway that foiled the battery’s escape from Barksdale’s Mississippians on July 2.

After a remarkable and successful life, Mr. Norwood passed away in 1914 at the age of 77 years and was buried in Bellevue Cemetery in Lawrence, the southern bullet that almost killed him at Gettysburg still lodged in his chest. Fortunately the remarkable story of his night on the field of battle and the boulder that sheltered him was preserved in the history of the battery written by Levi Baker, published in 1888.

Something about his comrade’s story must have inspired Holland who compiled a sketchbook of Gettysburg subjects soon after their visit to the field in 1883 that included water color illustrations of John Norwood and his protector- the large granite boulder and tall tree adjacent to Trostles’ orchard. The tree that shaded the injured soldier has long been gone from this site and though time and weather have played hard on this particular boulder, which fits perfectly in the field among other rocks and rounded blocks of granite that jut through the soil, it is different because it has a personal story. And now, a specific identity.

Like so many of the silent witnesses of the battlefield, it takes time and sometimes a good dose of luck to uncover that unique story and be able to share it. Mr. Holland and Mr. Norwood would not have it any other way.

-John Heiser

Gettysburg National Military Park

Author’s note: Richard Holland’s work fell into obscurity after his death in Brockton, Massachusetts, in 1905 though several paintings he did for the Brockton City Hall are still on exhibition there today. We sincerely thank Mrs. Selma McClintock for the loan of his sketches to illustrate our story.

UPDATE, May 2018: It was brought to the author’s attention that Norwood was a private, an artilleryman in the crew of the #5 gun, and not the gunner of the piece, so his title has been corrected in this story.

[i] Levi W. Baker, History of the Ninth Massachusetts Battery (Framingham, MA: Lakeview Press, 1888), p.75.

[i] Ibid., p.75

Thanks so much for the great story–another of the many small details that makes visiting Gettysburg NMP such a powerful experience.

Human interest stories such as this continue to fuel my 40 year old interest in Gettysburg. Well told, John. Glad we have historians of your caliber at GNMP.

This is a great post. I’ve forwarded to all of my Massachusetts (and Gettysburg) friends. Looking forward to visiting the rock and adding it to my collection (Anawan Rock, Hand Rock, Abrams Rock, etc.) As my wife asked one day when I returned from doing research: “See any good rocks today?”

Great post – really enjoyed it.

Wonderful story. Thanks for sharing.

A great article and one that brings to life the heroic actions of Gunner Norwood at Gettysburg. I will be sure to include a visit to Norwood’s rock when and tell Norwood’s story when our battery visits Gettysburg each year to honor the 9th Mass Light Artillery.

Capt. Elliot Levy, 9th Mass Light Artillery

Bigelow’s Battery

I’ve lived and gone to school in Lawrence , Mass. and when I was much younger worked for a year or so at Bellevue cemetery. My first trip to Gettysburg was for the centennial remembrances in 1963 with my father and three of my brothers ( I had just turned 13 ) and I have slides from that visit including one of the 9th Mass. Battery monument taken looking across the field toward the Trostle house. I now try to make it down twice a year. I’ve walked that field across which Bigelow’s battery retired by prolong and seen that rock but hadn’t ’til now known John Norwood’s story. Thank you. I’ll take a closer look this Fall , and also drive over to Bellevue and see if I can find that brave man’s grave marker.

Thank you for the fabulous article, John Heiser. This added some detail to the story that previously I hadn’t known and the Holland work adds another visual dimension to the story. I am hopeful that the Holland sketches might someday make their way to the NPS for viewing by future generations. I’ve been to the battlefield twice in the past 15 years to see the various positions of the 9th Battery. Interestingly, my father never spoke about Gettysburg — though his older brother and cousin knew some of the story and we have some artifacts from the period including a photo of John K. at the battlefield in 1883 with his two grandsons (one of whom was my grandfather). I’m the great, great grandson of John K. Norwood.

-John M. Norwood

West Des Moines IA 50265

Wow, so great to read your reply…and that you are a direct line to Mr. Norwood. I have a lifelong interest in Gettysburg, with several ancestors fighting there,…on both sides. My wife’s gr gr gr gr gr gr grandfather’s nephew, Lt. Crockett East, was killed serving with the 19th Indiana at McPherson’s Ridge….and I live in Waterloo, Iowa.